Preparing Students for Sustainable Jobs

A Conversation With Steven Brint

Steven Brint is a distinguished professor of sociology and public policy at the University of California, Riverside, and the author of “Two Cheers for Higher Education.” VEDP President and CEO Stephen Moret caught up with him on a recent trip to the West Coast to discuss his work in, and analysis of, higher education in the 21st century.

Stephen Moret: You had a chance to get to know Clark Kerr and work with him, I think, on at least one book. What are your reflections on the role he played in the development of higher education in California and the country?

Steven Brint: Clark Kerr was the most important figure in American higher education — and possibly global higher education — in the mid-20th century. He was very instrumental in the development of the California Master Plan, which created a three-tiered system in California. That was where you had community colleges, then the state colleges, and the University of California. That was emulated in many states outside of California.

Clark Kerr was the most important figure in American higher education — and possibly global higher education — in the mid-20th century.

He built the University of California. Seven members of the Association of American Universities are UC campuses. Berkeley, during his chancellorship, was thought to be the best balanced, outstanding research university in the country, which is quite an accomplishment for a public university when you have private universities like Harvard and Stanford.

I was fortunate to meet him when he was quite elderly. He gave the keynote talk at a conference I organized when he was 89 or 90. He spoke without notes, in full paragraphs. We marveled at his capacity, even at that advanced age. So, a remarkable person.

Moret: What was he like on a personal level?

Brint: I wouldn’t say he was a “life of the party” type of person, but he was genuinely interested and he made numerous inquiries, for example, about me and my family. I had the sense he was a warm, but obviously cerebral, person.

Moret: He passed away a little over 15 years ago. If he had a chance to come back for a day or two and observe higher education in 2019, do you think there’s anything that would surprise him, or any observations he might have based on your experience with him?

Brint: I think certain aspects of change since his death might come as a bit of a surprise to him. The connection of universities with the business community was not nearly as advanced, although it was happening in the early 2000s.

The role of universities in technology development obviously was also happening, but has continued and flourished. I would say also the global character of some American universities with branch campuses in foreign countries, lots of exchange with other countries, both scholarly and student exchange, that’s advanced quite a bit since his time.

I don’t think he would be that surprised because we’ve already been dealing with this since the 1970s, but trying to come up with other resources besides state funding. That has continued to be a big issue. Most trends that we’ve seen were products of the ‘70s and ‘80s when he was around.

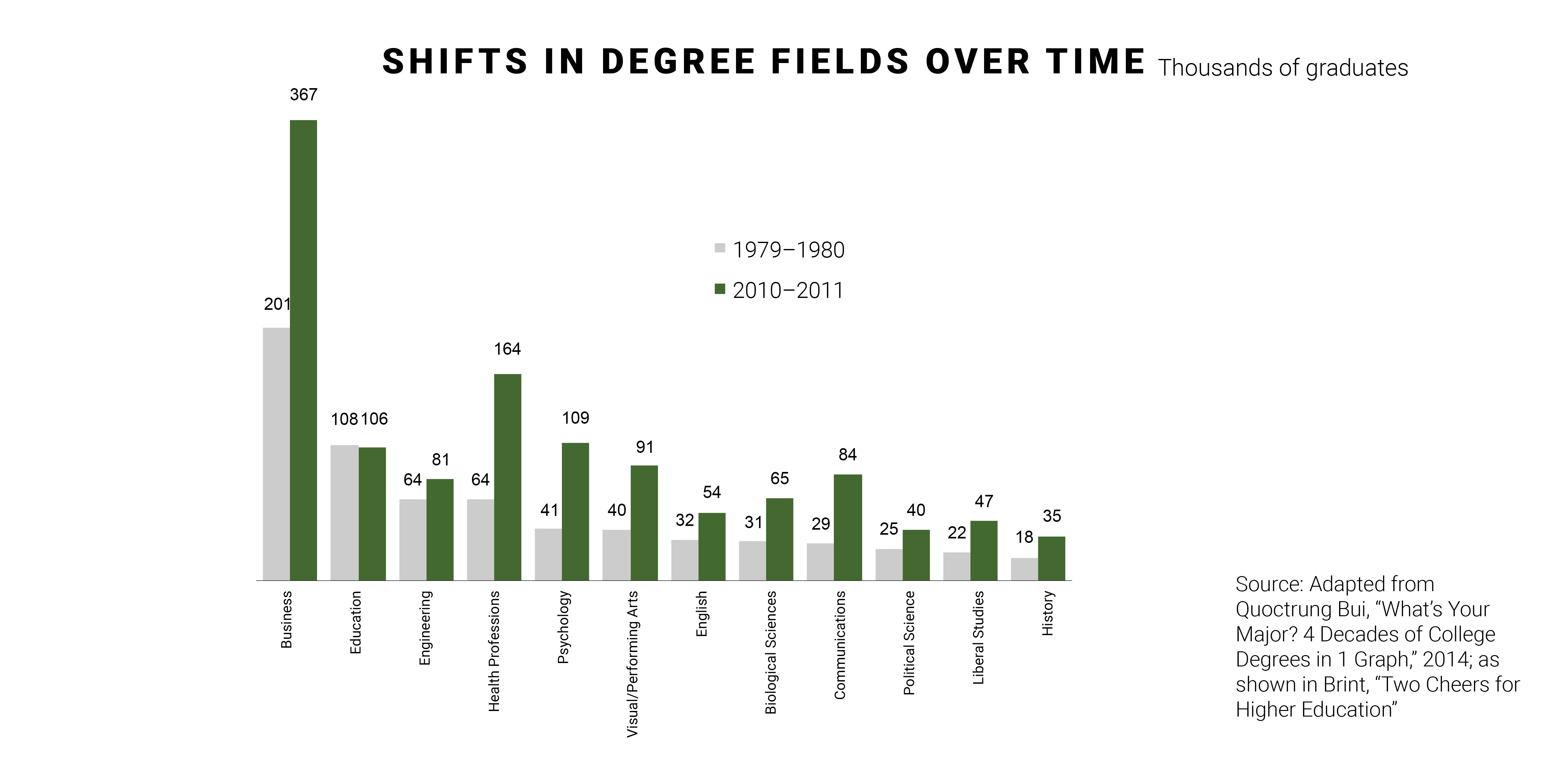

Moret: In 2002, nearly two decades ago, you edited a book called “The Future of the City of Intellect,” which had a big impact on my thinking about higher education. There was a chapter you wrote in that book called “The Rise of the Practical Arts.”

Around that same time, I read a piece by Dick Scott at Stanford. I’m forgetting where it was published, but he talked about the practical arts and liberal arts. He also made a distinction and talked about this third category, which he categorized as vocational programs. I think in your scheme this would essentially represent the newer entrants to the practical arts, things like parks and recreation management and construction services, which involve occupation-specific knowledge but maybe without as much grounding in theoretical framework.

Is there anything you want to share around that topic, as you think about the implications or the differences of these types of programs and the employment outcomes that they experience after the fact?

Brint: I think there are a couple of factors here. One is obviously market demand for different subjects. Another is the rigor of the subject.

If you look at pay scale, which is one of the ways you see the average incomes of college graduates, maybe the first 10 are all engineering disciplines, at mid-career. That’s a combination of very robust demand and rigorous curriculum that not every student can succeed in. We know that rigorous curriculum is not really in some way the key factor. Latin and Greek, for example, are very rigorous as far as demands on students, and yet you don’t have market demand.

Here’s something that’s interesting about study time and the expectations for analytical and critical thinking that we have looked into and in which we had surprising results. We felt it’s likely that analytical and critical thinking would be a bigger factor in the humanities and social sciences. Because they’re often taught in seminar-style classrooms, where there’s discussion of text and you have to write papers, where you compare and contrast and use evidence to support your arguments. At least, that was the tradition I grew up in, when I was taking humanities and social science classes.

We were very surprised in the study we did of the University of California, at least as far as the survey results were concerned. We didn’t see strong differences across disciplines in the analytical and critical thinking experiences that students had. We did see strong differences in their self-reported study time, not surprisingly, in the natural sciences and engineering. Reported study time was significantly greater than in other disciplines.

I think that’s a testimony to their difficulty. They’re maybe more rigorous and difficult in some ways, although I think it’s also worth saying that not everybody who can grind through an engineering curriculum would succeed in other fields. Most engineering students may not have the interpretive skills that you would need in a communications major or in other humanities. Students who do well in engineering may not do well in those disciplines.

And so I think one thing that’s wonderful about universities is that there’s a place for students who are different. Maybe it’s the way their brains are wired or their developed skills, what have you. There’s a place for them. But it’s true that the place in the labor market is not equal for all of these disciplines. Some part of the problem that we see in the humanities and other disciplines now is that universities are oriented toward those that have labor market demand.

Moret: When we talk about connections between higher education and the labor market, it’s largely grounded in this notion of human capital development. We tend to think of that as something the education system has a monopoly on. But as we look at people and their development in the long course of their career, a tremendous amount of their human capital development actually happens in the context of their work life.

One of the things I came to appreciate more about these ranges of different employment outcomes for graduates in different degree fields is that a lot of the mid-career earnings advantage of engineering grads, for instance, is not so much that they studied engineering, because many aren’t working as engineers 15 years later, but rather that because a large percentage of them secure college-level employment, they’re in the types of occupations that further develop that human capital and give them access to other college-level jobs.

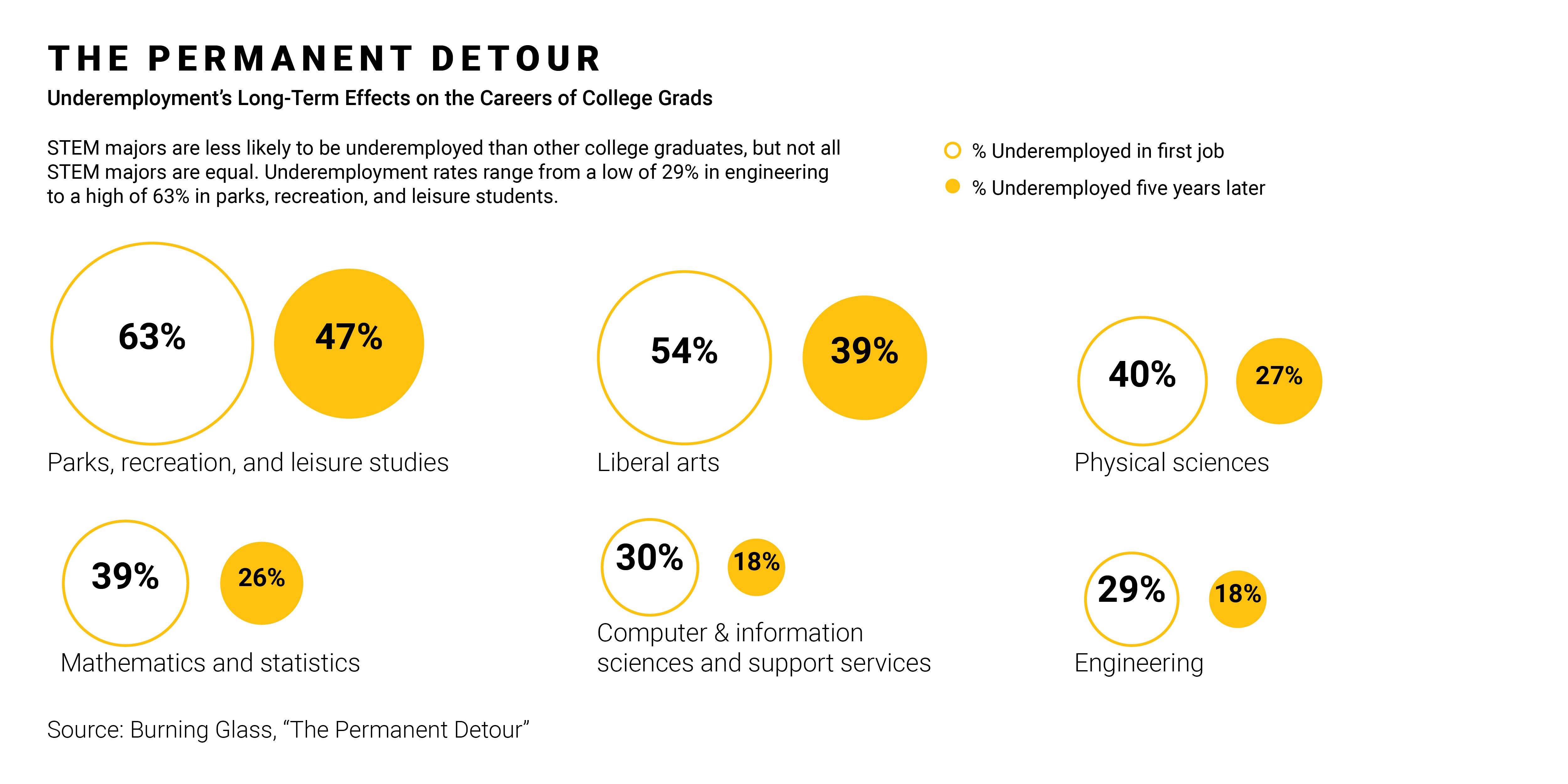

There was a report last year by Burning Glass, a big data analytics company, called “The Permanent Detour.” It was a synthetic longitudinal study where they analyzed millions of résumés of college graduates. Some of what they found wasn’t new. We’ve known about underemployment for a long time. They found what underemployment looked like, and it was pretty sticky.

One thing that's wonderful about universities is that there's a place for students who are different. Maybe it's the way their brains are wired or their developed skills, what have you. There's a place for them. But it's true that the place in the labor market is not equal for all of these disciplines.

It wasn’t just that a large percentage of college graduates initially are underemployed, it’s that most of those who initially don’t get a college-level job essentially don’t get one later on. So, while unemployment starts off at 40% or so, it goes down pretty quickly. But it actually levels out at around 30% for the adult, full-time employed population of bachelor’s grads and above in the U.S. Part of it is this issue that if folks don’t attach relatively quickly to a college-level occupation, they end up not getting there.

When you think about underemployment, what I’ve come to believe is that this transition point — we talked about colleges preparing people for their seventh job — there’s a lot of truth in that. But the first job is really important in setting a trajectory for the future.

Brint: When I was doing research for my book, “Two Cheers for Higher Education,” I ran into work by the Federal Reserve in New York that showed very high levels, like you report, of 40% or more initial underemployment. Historically, that's melted over time, but it may be for new cohorts it's not melting. As you say, that's a huge issue.

If you have 30% of students unable to move out of that underemployed non-college-level job, and they have accumulated debt, and they've gone to college with high expectations, that's an issue. It could be that some of the public opinion we're seeing now that's a little more critical of higher education is connected to that sticky problem.

This is not a phenomenon that's just due to higher education. Obviously, it has to do with the structure of the labor force, how that structure is changing, and the number of college-level jobs available. But universities and colleges need to be aware of what's happening in the labor market and take it into account as they're preparing students.

Moret: I want to shift gears to your terrific new book, “Two Cheers for Higher Education,” published in 2018 by Princeton University Press. It’s gotten a lot of great reviews. One of my favorite quotes was Steven Mintz with Inside Higher Ed, who said, “The most thorough, sweeping, and balanced book that I’ve read on the strengths and weaknesses of contemporary colleges and universities.”

Could you tell us about the title? What’s that about? Why did you write it? What are the big things you explore in the book?

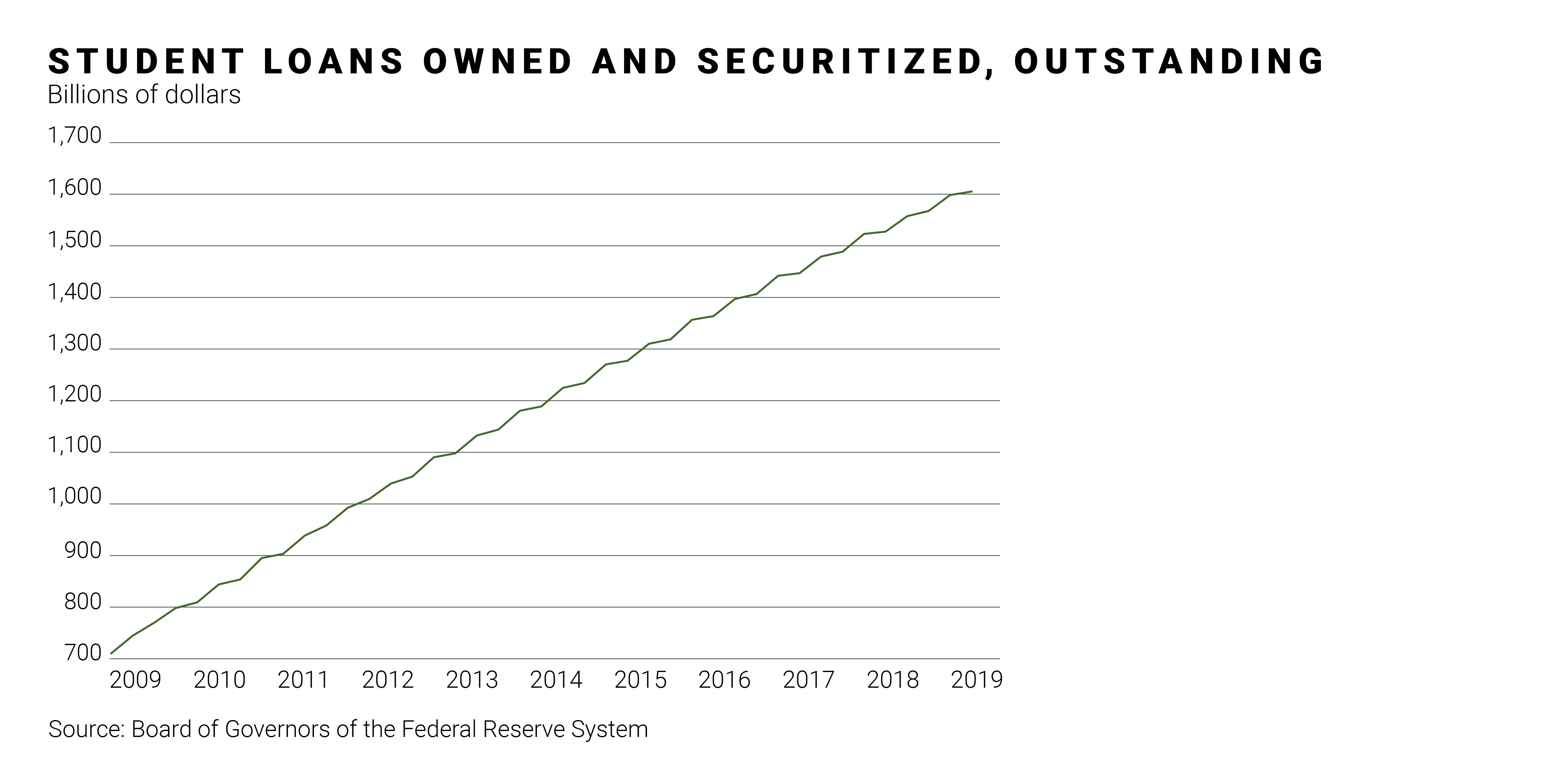

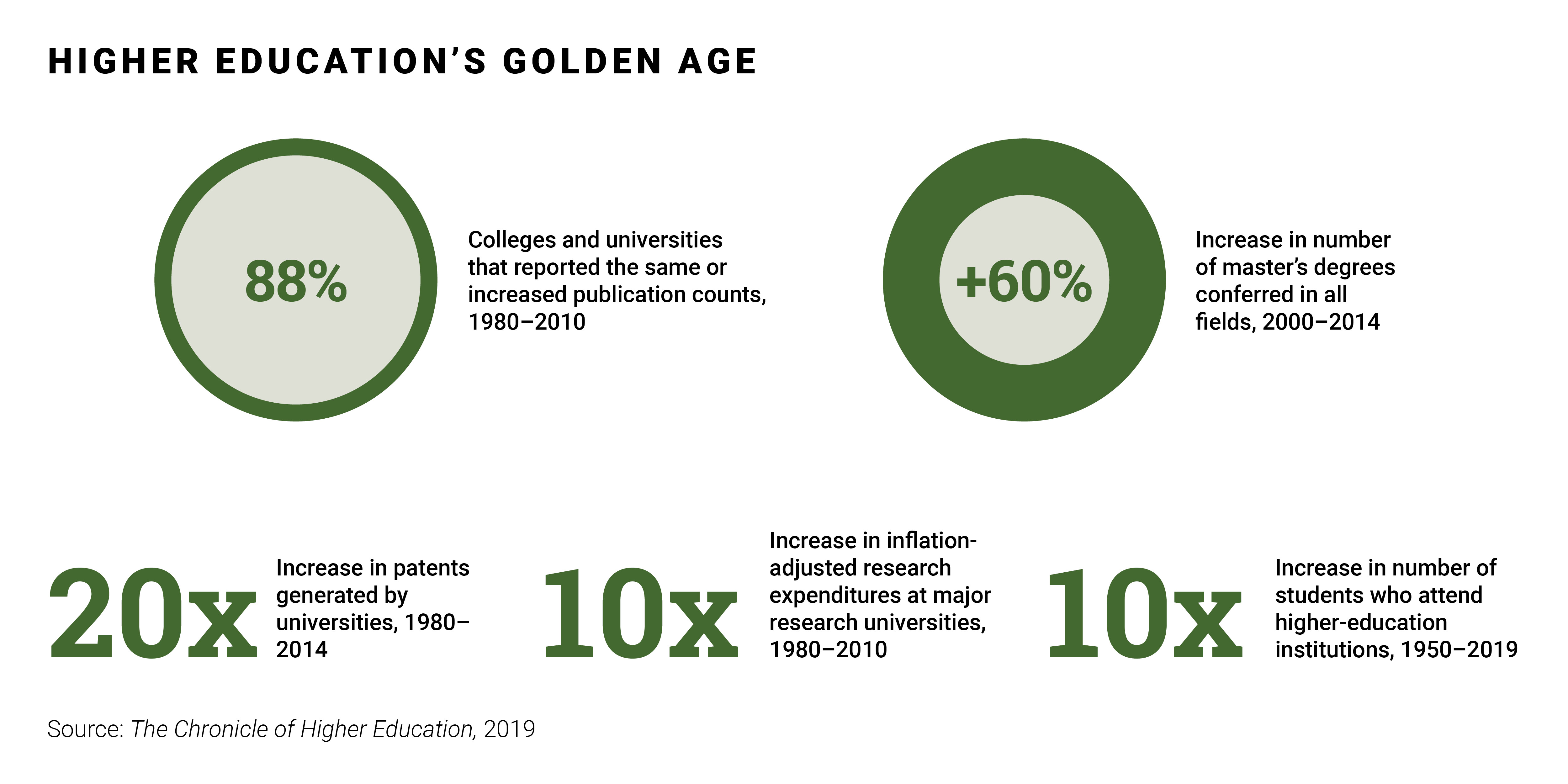

Brint: “Two Cheers for Higher Education” is a title that was thought of against the backdrop of higher education scholarship, which tends to be very pessimistic about the state of higher education. The thoughts are that students are deeply in debt, tuition is going up, some of these issues of underemployment, many adjunct professors teaching classes. This is not a success story.

But when you look at the data, you see that, in fact, American higher education is doing quite well as an institution. For example, R&D expenditures in constant dollars went up more than nine times between 1980 and 2015. The number of published papers went up at least four and a half times during that period. Citations are harder to count because they increase slowly, but we don’t see any reason to believe that they haven’t also increased.

We looked into important inventions, and even though corporate R&D is three or four times the level of university, by my estimate, universities were responsible for about 40% of the most important inventions during the period we looked at.

A lot of our consciousness is shaped by ideas that come out of universities. Everybody now uses the terms “emotional intelligence” and “social capital.” These ideas didn’t come from out of the blue, they came from university professors and university research.

The classroom is one arena, and the most important one, for learning. But there are other arenas for learning on the university campus.

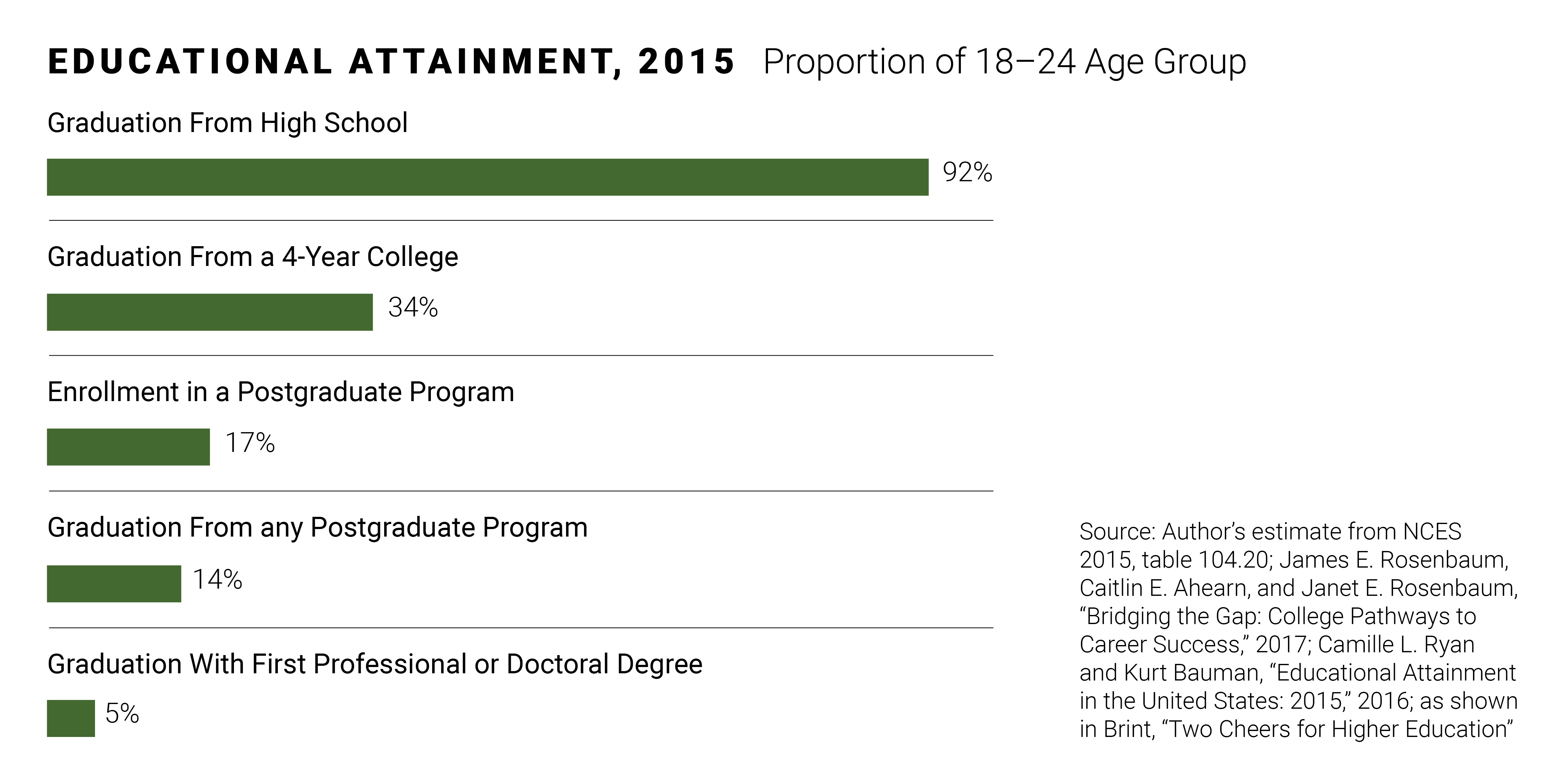

We also looked at enrollment, which I think has nearly doubled between 1980 and 2015, the years I looked at in the book. It’s the same at the graduate level. If the institution were failing as badly as many scholars feel, and if it were on the brink of being reorganized by online entrepreneurs, I would doubt that there would be such robust growth in enrollment.

But it gets only two cheers because of problems we haven’t solved. Perhaps the most important one is the quality of teaching and the amount of learning in higher education. Many students aren’t learning as much as they could. We have problems of cost, affordability. We have online competition that threatens to erode some of the developmental advantages of the physical campus. We have the growth of an adjunct labor force that’s very poorly paid. And we have some speech controversies. I think there’s some truth to what has been said about the climate for speech being non-conducive for certain ideas.

So there are reasons for concern. Even though we see a very successful institutional arena, only two cheers because we have a long way to go to solve some of our problems.

Moret: When I think of discussions about higher education in the U.S., we get a lot of attention around educational attainment and cost and student debt.

But compared to those two very important things, the amount of focus on learning is way, way behind. In fact, one of the major national higher education institutions a few years ago actually raised an alarm, saying it’s great that we want more people to go to college, but we need them to actually learn the critical thinking and communication skills that we espouse when we talk about higher education. Why do you think there’s not more attention on that topic?

Brint: Now, there’s attention also to graduation rates. That’s good. But I couldn’t agree more that sometimes they say equality without quality is hollow. There’s no doubt students could be learning more in college. And we have to look at it in a complex way, because they’re learning outside the classroom, too.

In fact, I just published a paper about the co-curriculum of student clubs and organizations. Students gain some adult skills in those arenas, too. They learn how to run meetings, recruit new members, put on events. Many students have those experiences, at least students who go to big universities. There are sometimes as many as 1,000 clubs or more at UC Berkeley. At some of these colleges, there’s one club for eight or nine students. You really have an opportunity there.

So the point is that the classroom is one arena, and the most important one, for learning. But there are other arenas for learning on the university campus. The issues are profound as far as learning goes. There’s very good evidence that students are not reading much of the assigned work.

You can do things to increase student engagement and participation, which is one factor. If students are just passively listening, that’s not good. You need to break up the classes, have them talk about problems, and then report out and answer questions constantly in class. Many techniques encourage that. I even give out points to students who have not talked up if they’re willing to hazard an answer to a question. We do a lot of that.

Accountability is important, too. Frequently, if not every class session, you have to ask students to write 100 or 150 words about what they read. That creates an accountability for reading. It’s very hard to write well unless you read, and you read deeply.

I think it really is up to the individual instructors, with the institution’s help, to take what’s being learned in the research literature, disseminate that, and then help professors bring it into their practice. I also talk about student evaluations of teaching. Students are good evaluators of some dimensions of teaching, but not all. They cannot say whether they are learning as much as they could be learning. I write positively about the Weiman-Gilbert Teaching Practices Inventory, which allows college teachers to see whether they are following practices that the research literature consistently shows to have a positive impact on learning.

Moret: You talk about how the universities negotiate a variety of competing demands and missions. As I think about where learning stands, it seems part of it has to do with where administrative leadership is focused. Particularly with public universities, states have largely retreated as a primary funding partner. We move toward state-affiliated versus state-funded institutions. University presidents increasingly are having to spend a large percentage of their time on fundraising and external affairs.

It seems that maybe the balance has gotten off in terms of the quality of the learning environment and supporting learning, as in competition with some of these other missions of the institution.

Brint: I do agree with that. Of course, there’s a lot of variation from institution to institution on this.

They’re very much changing, with, for example, more market-based master’s degrees at liberal arts colleges. But if you look at it from the administration’s point of view, trying to make payroll, and do all the things universities are asked to do, including compliance with a lot of regulation, they require robust growth in several different resource bases. That’s why universities chase donors and contracts and sell services to other entities.

One of the easiest ways to raise additional revenue — at least in areas of the country where we see population growth — is to grow the size of the student body and bring in more state dollars if you’re public, but also more tuition dollars. Even very selective places like Princeton and Yale have grown a little bit over time, and Stanford has grown significantly.

Again, looking at it from the administrator’s point of view, bodies are important. Human capital development and cognitive development, from the administrative point of view, may be less important than the flow of bodies into and out of the institution. I think they can say, “Well, look, our graduation rates are pretty high,” but what can students do who graduate? That’s left as a black box. I think the incentives and pressures on administrators are to expand resources, and one way to do that is expand enrollment. That doesn’t come necessarily with the proviso of how much we have to contribute to cognitive and human capital development. So it’s up to the professors and support staff of the learning centers and the academies of distinguished teachers who help improve teaching and learning. That’s where that focus is, the traditional aims to develop competence and help students develop their cognitive capacities. That’s where it’s going to have to come from.

The incentives and pressures on administrators are to expand resources, and one way to do that is expand enrollment. That doesn't come necessarily with the proviso of how much we have to contribute to cognitive and human capital development. So it's up to the professors and support staff of the learning centers and the academies of distinguished teachers who help improve teaching and learning.

Moret: In the book, I got the sense you suggested that as universities have grown and become more accessible to a broader socioeconomic strata in the country, there’s been a bit of bifurcation, maybe even in academic expectations. It seemed as if you were suggesting that in some cases there are less rigorous tracks within degree fields. Does any of that resonate with what you were trying to say?

Brint: There are less rigorous tracks for sure. I’ll cite Elizabeth Armstrong and Laura Hamilton, who talk about “business lite” tracks like recreation and fitness and sports management, and even aspects of marketing and communications as being low-expectation fields, where students often can get by on the force of personality and even physical appearance.

So there’s that set. I think there’s another set of disciplines in cultural studies fields that are often reputed to have fairly low expectations of students. So, yes, I think there are differences among the disciplines as far as that’s concerned, and they’re not entirely tied to the market, interestingly enough.

If you go into business school, there are aspects that are quite rigorous. I think finance, accounting, probably strategy. But other parts of business school may not be. It’s often said business school is a networking opportunity and not necessarily a cognitive development opportunity for some students. And yet, there’s demand for business students.

For sure, what you’re saying is right. There are disciplines that early in our conversation you identified as vocational disciplines. I think that’s where we have the biggest issues with respect to the bifurcation you identify.

Moret: One of our big interests in Virginia is leveraging higher education to drive quality job creation and economic growth in the Commonwealth. Virginia has a very strong economy. It’s a wealthy state, overall. It has somewhat underperformed in job growth over the last decade or so, largely tied to our over-reliance on the federal government. When you have BRAC, we tend to have a slowdown.

But on this theme of leveraging higher education for economic development, when we had the opportunity to compete for the Amazon HQ2 project, we decided to make our case primarily on a historic investment in public universities, colleges, and community colleges to expand computer science and related education to support not just Amazon, but the whole tech sector.

What do you think states and universities could be doing to better leverage the potential for higher education to contribute to region and state economic development?

Brint: There are some good examples out there. The Georgia Research Alliance is a program that builds around star scientists who are recruited into the major universities in Georgia and are provided with funding as well. I think they have contributed for graduate students and post-doctoral researchers a lot.

Part of the deal with the Georgia Research Alliance is the expectation that new technology development will be part of the agenda for these professors who are hired through the program.

New York state has had these Centers for Excellence for a long time, and I think some of them have been quite successful. There’s a big nanotechnology corridor in Albany, for example. California has had the Centers for Science. Some of them have been very successful.

By and large, only a few states have seen higher education as a huge part of state economic development. Some campuses, though, have also made this a priority. And you’ve seen a lot of spin-off business development on certain campuses like Austin and Ann Arbor. Salt Lake City is an interesting one. Boulder, Colo., is interesting.

Those universities — through their engineering and natural sciences — they’re not always started by faculty — sometimes graduate students — they have developed industrial clusters. They try to foster them through business accelerators, incubators, and other programs like that.

Part of what I wanted to get at in the book was, where do we see this happening and where do we not see it happening? There are some issues that universities have to solve, such as, is there venture capital nearby? Is there good transportation to venture capital if it’s not nearby?

One problem at places like Cornell and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign is that they’re in rural areas. There’s not fantastic transportation to large urban areas, to venture capital. They have great scientists and engineers there, but they’re isolated. Cornell actually moved to New York City to start Cornell Tech because they couldn’t make it happen in Ithaca or in the regions near Ithaca.

Moret: This is one of the great challenges of universities. The university by itself, in some ways, is not enough. You need capital, you need talent. Otherwise, you end up producing IP that gets commercialized in other places.

Brint: Exactly. Some of our greatest universities haven’t been terribly successful in the economic development arena.

Another great example is Penn State. Tremendous university, but located in the middle of Pennsylvania and not near anything else. You can go to Penn State and you’ll see very few firms in State College. Yet, you have this tremendous talent base.

So, location has something to do with it. And also the traditions of the university have something to do with it. Johns Hopkins University is an important example. They’re in the city of Baltimore, but they have almost nothing to do with Baltimore because they’re primarily interested in academic acclaim and government research contracts.

They’re the ivory tower, in a way. Other institutions are similar. The University of Chicago is one.

It’s a very mixed and interesting situation. I would say at the state level there are some successful examples. But most of these ran into the same kinds of problems. For example, you get a new gubernatorial administration, and the new administration has new priorities and doesn’t like what the old administration did.

Also, firms sometimes have very short time horizons. They will invest for a little while, then they’ll decide this investment isn’t paying off. It’s a tricky terrain to navigate.

Moret: If you look at the geography of economic growth in the United States, we see this separation happening where the big metros are doing the best, midsized metros second-best, small metros third, and then at the bottom are the rural and unattached localities.

I recently thought about big universities vis-a-vis small colleges. Maybe in some ways this scale question renders itself in a similar fashion. Bigger schools can offer students a no-compromises experience. You have all these different academic disciplines, the full variety of extracurriculars that you talked about. You could have an honors-college experience in the context of the big state school.

Do you think that this bifurcation of economic growth in metro areas could almost be applied in similar ways to the more acute challenges that some small colleges are having in comparison to our bigger schools?

Brint: I think a couple of things are going on. One is that large universities are attractive for a whole variety of reasons. For some students, it’s the football team. For others, it’s the variety of disciplines that they can study, or the co-curricular, extracurricular, activities. The college-town atmosphere. They have a lot going for them. They’re usually much better supported, too, because they have philanthropy and they’re usually better supported by the state when there is good state funding.

The other thing that seems to be going on is that in the places losing population, the colleges are struggling. It’s especially the regional comprehensive centers that are struggling. Often, the big state university is doing okay. So we’ve seen mergers, we’ve seen some closings. It’s very unusual for a public college or university to close, so mostly they’re merging.

I haven’t done an analysis of this, but I’m pretty sure there’s a geographical aspect to this, and it’s related to population growth, population decline, or stasis.

We’re definitely getting uneven development on several levels in the United States at this moment. But I think it’s interesting — to circle back to Clark Kerr — that in his time, it was thought that the big universities were problematic because they were too big and students felt anonymous.

You remember, even the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley was about students being treated like, or processed, as if they were cattle or something like that. They said that one of the phrases was, “Don’t fold, spindle or mutilate,” like they were punch cards. In fact, it seems those concerns were unwarranted because the places that have the greatest attraction now are, just as you say, the large, vibrant research universities.

Moret: Congratulations on all the great things you all are doing at UC Riverside. I hope that we’ll be able to stay in touch in the future.

Brint: Me, too. It’s been a pleasure. Thank you, Stephen.

For the full interview, visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts