Exploring the Practical and the Fantastical in 5G

Across the wireless industry, 5G — the fifth-generation technology standard for broadband cellular networks, meant to deliver higher data speeds, lower latency, more reliability, and higher capacity — has been not just the next big thing, but a family of next big things. On smartphones, faster, higher-capacity service could let us spend less time waiting for new apps to download. In homes, “fixed wireless” 5G connections could give residents more choice in broadband providers. And in offices, factories, streets, and other non-traditional settings for wireless connectivity, 5G’s potential to connect not just people, but devices, could rewrite how industry and infrastructure function.

The open-ended nature of that potential has led to many 5G forecasts that might as well have come sprinkled with fairy dust — even as early hype about 5G putting self-driving cars in people’s driveways or empowering robot surgery from hundreds of miles away has yet to pan out.

But while previous wireless standards were instrumental in paving the way for consumer breakthroughs like messaging and video chat, 5G is poised to make profound differences in people’s lives. Across Virginia, developers, researchers, and entrepreneurs are finding innovative ways to use this next generation of wireless broadband.

Precision Trucking at The Port of Virginia

At the Virginia International Gateway container terminal in Portsmouth, a lack of technology is not the problem. Instead, the potential issue is people behind steering wheels.

“There’s been a growing concern about whether there’s going to be enough trucking available over the next five to 10 years,” said Rich Ceci, senior vice president of technology and projects at Virginia International Terminals, LLC, a subsidiary of the Virginia Port Authority. The port approached the U.S. Department of Transportation about setting up a pilot program to experiment with autonomous trucks, ultimately receiving $4 million to research those possibilities.

The program is set to run for four years, but one key early step won’t require waiting for advances in autonomous truck operation. Instead, the port aims to use 5G to locate human-operated trucks far more precisely — data that’s already useful for routing human-controlled trucks within the port and that becomes essential once those trucks are unmanned.

The port currently uses differential GPS — the satellite-navigation system augmented by local base stations — to determine the position of vehicles down to 10 inches. The hardware required for that is aging, and using 5G signals to calculate location offers the possibility of much more accurate location.

It helps that the port already has the infrastructure to support cell sites for a dense 5G network using millimeter-wave signals — the fastest variety of 5G, but also the variety with the shortest range. The light poles in the facility are a 5G-ideal 600 feet apart, while the port has over 50 miles of fiber on the property.

“We’re probably the only terminal on the East Coast that can do this project,” Ceci said. “The other terminals just don’t have the technology to interface with the truck like that.”

That should leave the port well situated for increasingly advanced 5G developments, eventually including helping trucks navigate its premises autonomously. That, in turn, could pave the way for safe deployment of self-driving trucks in defined places and times — a simpler problem to solve than training a car to drive itself on every street, in all conditions.

Ceci suggested one scenario of automated delivery by caravans of trucks on highways: “Imagine an autonomous vehicle train that starts at night when the traffic lets down and runs all night.”

A Smart City Near Data Center Alley

Even before Amazon announced plans to build its HQ2 project in the neighborhood now branded as National Landing, the leading developer in Crystal City was planning a major connectivity upgrade to take advantage of a non-obvious resource: fiber laid underground years ago for Arlington County’s government.

“There was already fiber in the ground,” said Evan Regan-Levine, executive vice president for strategic innovation and development at JBG SMITH Properties, Inc. (JBGS). “We could definitely ensure massive coverage.”

The county government had deployed that fiber both to connect offices and schools and as a bit of future-proofing, leaving capacity — both fiber JBGS could lease and space left open in the original conduit for additional fiber. Regan-Levine estimated that this saved the company a couple of years of work.

JBGS also did something unusual for any development firm: It bought its own spectrum, making a $25 million purchase of seven blocks of 5G-ready Citizens Broadband Radio Service spectrum in 2020 at an auction run by the Federal Communications Commission. In July of 2021, it signed up AT&T as its smart-city partner.

“We’re not intrinsically technologists,” Regan-Levine said. “But we know how to make enabling investments that will benefit our customers and deliver competitive, cutting-edge products for them. National Landing will be the prototype for how cities will look in the future.”

The first output of this effort will be high-speed millimeter-wave 5G running up and down National Landing. After that will come two compact data centers that JBGS’s commercial and institutional tenants can use to host applications that they want to make available throughout the neighborhood.

“Whatever high-end application you want to do, you can put it in this center,” Regan-Levine said. “That lets you access it from any of your buildings.”

In the short term, that means bandwidth for applications including computer vision, augmented reality, and virtual reality; looking at the longer term, companies working on critical U.S. Department of Defense projects could benefit from the extra computing power. The fiber underlying this digital infrastructure also allows some of the fastest possible access to the vast arrays of data centers to the west in Loudoun and Prince William counties.

Spreading Street Smarts

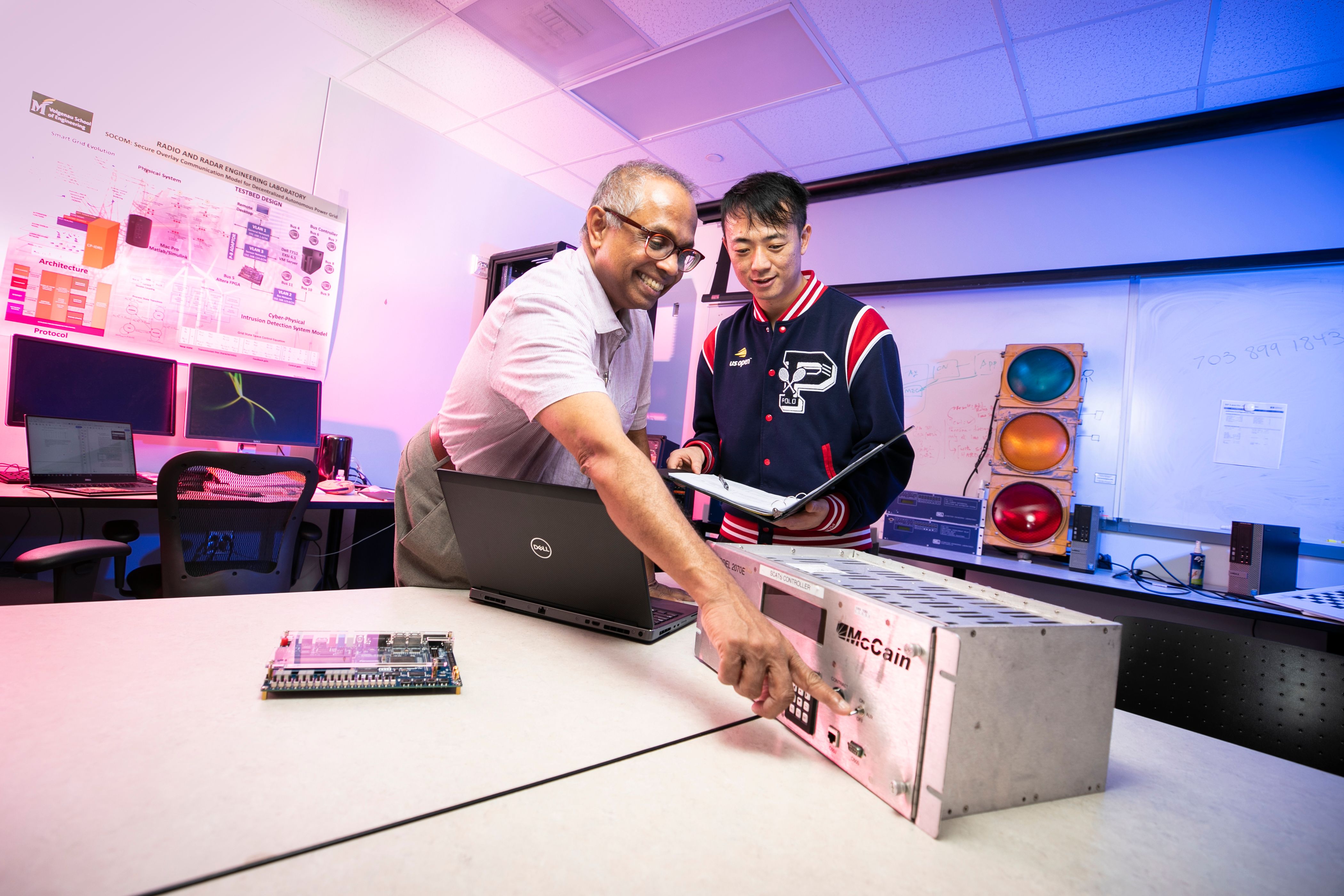

Cars have become increasingly smart, but they’re still not good at sharing those smarts. Duminda Wijesekera, a professor of computer science at George Mason University’s Volgenau School of Engineering, is working on ways to let more drivers — and, someday, autonomous vehicles — learn from others’ road experience.

“Look at the wealth of information inside the automated braking systems controller. It knows if one side of the road is slipping,” he said, referring to the systems that have been standard on cars for decades. “If every car translated this, everybody else would have immense capability to avoid slipping and sliding.”

But the system Wijesekera and his colleagues are working on doesn’t assume that every vehicle will have the ability to share its sense of the road via 5G. Instead, they envision having enough vehicles share road data with existing roadside terminals. They would then leverage 5G’s mobile edge-computing capabilities to analyze that data, derive a ground truth, and communicate that to other road users through digital road signs.

Wijesekera noted that this architecture would lend itself to early adoption in fleet use cases, such as buses, police cars, and even delivery robots. He also emphasized how the system should work on mid-band frequencies, not just the fast (but scarce) millimeter-wave frequencies so often highlighted in 5G hype.

It’s yet another example of treating 5G as a gear in a machine, not a goal in itself. As Wijesekera put it, “Just because you have 5G doesn’t solve a lot of problems.”