The Future of Cities

A Conversation With Joel Kotkin

Joel Kotkin is the Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University in Orange, Calif., and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. Described by The New York Times as “America’s uber-geographer,” he is an internationally recognized authority on global, economic, political, and social trends.

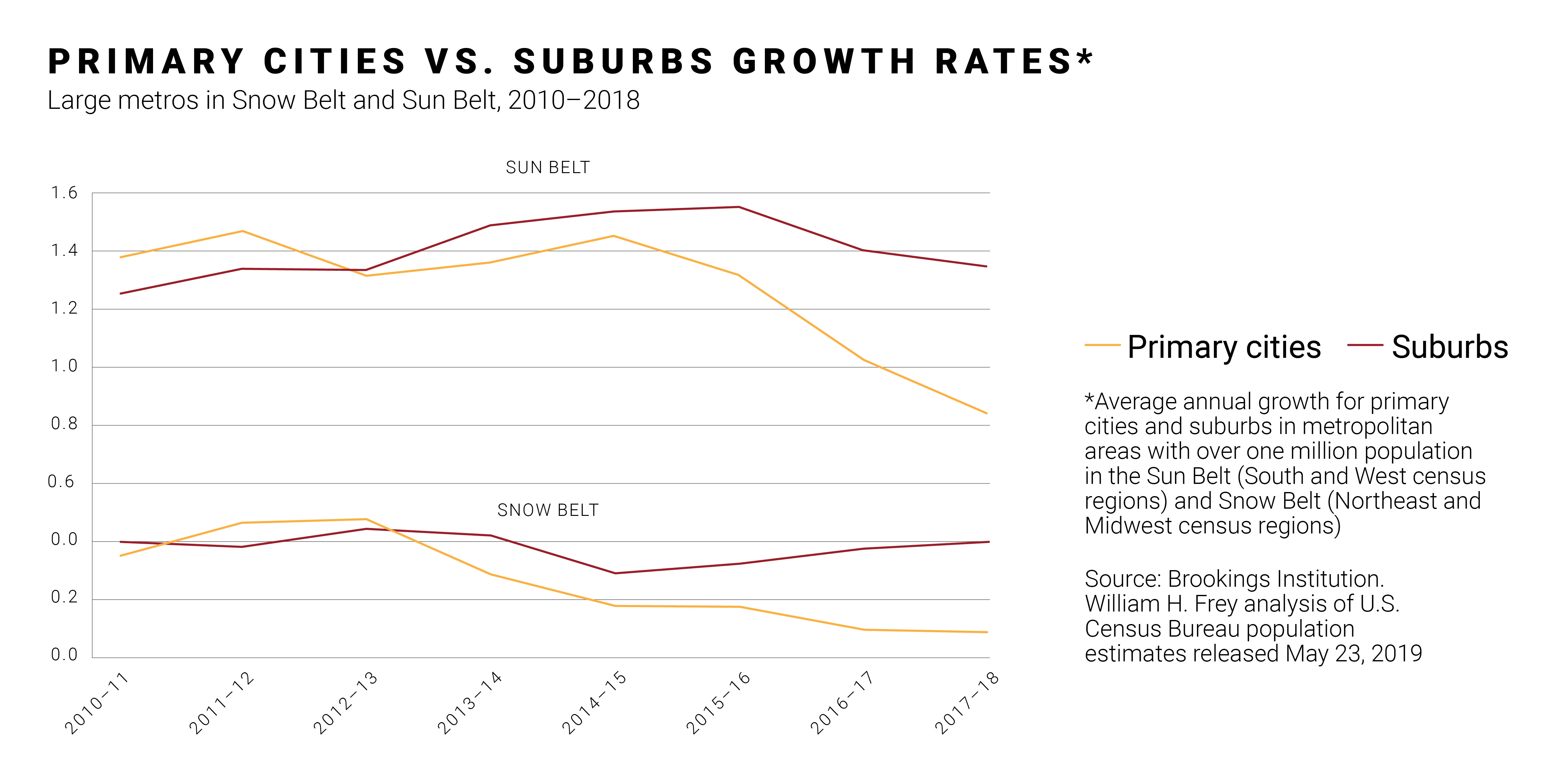

Stephen Moret: There were some really interesting pieces in The New York Times recently. One was authored by Amy Liu and one of her colleagues at the Brookings Institution. They talked about the diverging economic fortunes of regions in the United States. Essentially, the big metros in general have been experiencing the most growth, midsize metros are second, then rural areas connected to the metros, and then detached rural localities. You’ve got this real separation or stratification of employment growth. I’m curious about your observations on that and how, in light of the big forces driving those shifts, you think communities, regions, and states could better position themselves for growth.

Joel Kotkin: This certainly was the case over the last 10 years. But if you go back another 10 years, smaller communities, particularly more midsize areas, were doing better. New demographic data, which is probably the best thing to look at, is showing growth is now stronger in midsize metropolitan areas than in big ones.

The big ones, you have to separate out. Houston, Dallas, Nashville, and Orlando are doing really well. New York is kind of the national average. Los Angeles is generally below the national average. So, it’s not a single story, and I think the migration trends and job trends are not as clear and as hierarchical as most planners would like them to be. People aren’t as stupid as planners think they are.

Moret: One of the things I thought was really interesting in your book, “The Human City,” was the many, many references to Singapore. It really featured prominently. It’s a market that I’ve long been impressed with from the perspective of their transformational economic shift over the last few decades. You’ve been involved with Singapore for a very long time — I think going back to the early ’90s. From an economic policy and economic development perspective, over that long arc of time, what have they gotten right that so few places around the world have been able to achieve in terms of going from, really, a Third World country to one of the top five or so wealthiest places in the world?

Kotkin: With Singapore, you have to start with the old saying that the threat of hanging tends to concentrate the mind. Singapore became independent under the worst of circumstances. It was an ethnically diverse place that was poor. When the British pulled out, they were really lost. Malaysia essentially kicked them out. What I think is brilliant is they said, “Okay, what is it that we have?” What they really have is human capital, particularly Chinese human capital, which means tiger moms.

The second thing is they have a fantastic strategic location. Obviously, the port was going to be important. Businesses depended on that strategic location. Then they started to move toward infrastructure, like the airport and having a great airline. If you’ve flown Singapore Airlines, you’d know what I’m talking about.

They also managed their ethnic diversity really well, but not in a way that would be constitutional in this country, probably. For instance, they’ve tried to mix various ethnic groups in housing. I look at it as a social democracy using capitalist methods. The idea of using capitalism to bolster social democracy is really what I’d like to see more of in this country, but we’re not doing that very well.

Moret: When I travel the world, I ask executives of big, multinational global companies what development agencies have impressed them the most in their own travels. Those who feel like they have enough context to answer the question mention the Singapore Economic Development Board 95% of the time.

Kotkin: Also, what they did was deal with the fact that they had very limited space. When you say you might advocate dispersion in this country or Australia or a country with lots of land, Singapore had no choice. What they’ve done is, instead of making people live in tiny spaces, they built public housing that they then allowed people to buy. That public housing is considerably bigger. The average apartment in Singapore is on average twice that in Hong Kong, for instance. I think they’ve done a lot of really good thinking about things, and then they understood in the long run that their human capital was going to be the thing they had, and also a rule of law and predictability. There’s a cleanliness, there’s an efficiency that you get in Singapore. I think it’s the best-run city in the world.

New demographic data, which is probably the best thing to look at, is showing growth is now stronger in midsize metropolitan areas than in big ones.

Moret: Part of that has to do with how they think about hiring and compensating their civil servants, right?

Kotkin: Yes. This was something Lee Kuan Yew has written about and I think it’s very evident. The Mandarin class in Singapore is very well compensated, with the expectation that you’re not going to need to take a bribe. If you go to the exact opposite end, to Mexico or India where civil servants are paid very badly, of course they’re going to take bribes. You don’t have to be a genius to figure this one out. So, I think that they made a conscious decision that they were going to get really qualified, good people.

I think Singapore made an effort to look at their situation and to change over time. They realized initially that manufacturing was something where they had a comparative advantage. Now, they knew that once China was opened up — and Korea and Taiwan — they really couldn’t compete except at the very high end. So, they moved more and more toward high-end electronics, a lot of biomedical, tech, finance.

[Kotkin] weaves an impressive array of original observations about cities into his arguments, enriching our understanding of what cities are about and what they can and must become.

They had a really good strategic vision. But the thing that keeps it together, and what we miss in this country, is any sense that we want to develop an economy that has a place for the vast majority of people. You take a society like Silicon Valley, the very top has done really well and everyone else has done worse. Poverty in many ways is worse. Homelessness is worse. All amidst one of the greatest economic booms in history.

You create wealth in the aggregate, but, as I would put it, people don’t live in the aggregate. They live their individual lives. I know many of my students here who come from the San Jose area say it has actually been very tough for their families over the last 10 to 20 years. San Jose had been a very middle-class place before.

I think that what one of the things Lee Kuan Yew, again, out of necessity, understood is, in order to have a workable social order, you have to have a certain degree of wealth distribution that’s tied to some idea of social justice. They would never accept the idea that you shouldn’t work. I think that would be completely culturally unacceptable.

Moret: One of the things I’ve observed about Singapore that I find really remarkable is they’ve combined two different development approaches into one. In the United States, for example, we could look to places like Boston or Massachusetts, some of the higher-cost, more progressive states that put a tremendous amount of money into education and infrastructure. But they do very little to attract business or provide incentives.

Other states, such as in the Deep South, perhaps haven’t invested enough in infrastructure and education, but are very aggressive about attracting industry. Singapore has actually done both. They’ve created a world-class business climate with tremendous investments in infrastructure and human capital development, but they also, for strategic economic development opportunities, will make enormous investments and incentives if they think a project is strategic to where they’re trying to go.

Kotkin has a lot to say, and it demands a hearing. Wholesale reassessment of the role of our cities and the areas around them is overdue.

Kotkin: I see some analogies in the U.S., particularly in Texas and North Carolina. Those are two states I would immediately shout out. One, they’ve invested tremendously in their education systems. They still play the incentive game but, fundamentally, they’ve done both. In Texas, they’ve done it on an enormous scale.

I was just speaking at Texas Tech, which is in Lubbock. It’s a gigantic university churning out thousands of skilled engineers every year. We always talk about the University of Texas at Austin, but you have to look at Texas A&M and Texas Tech as real drivers. What’s interesting is that California used to do that. California also had a very welcoming business climate at one time but, obviously, not anymore.

Moret: It’s hard to believe now, right?

Kotkin: It is hard to believe. But we also invested in our education system, and not just the University of California, Berkeley, but also the community colleges and state colleges. You have to have both. If you just have an education industry and you don’t have places for those people to go, they leave.

Moret: That’s right. Especially the highly educated.

Kotkin: Massachusetts hemorrhages people, and now California. We’re now educating people who go someplace else.

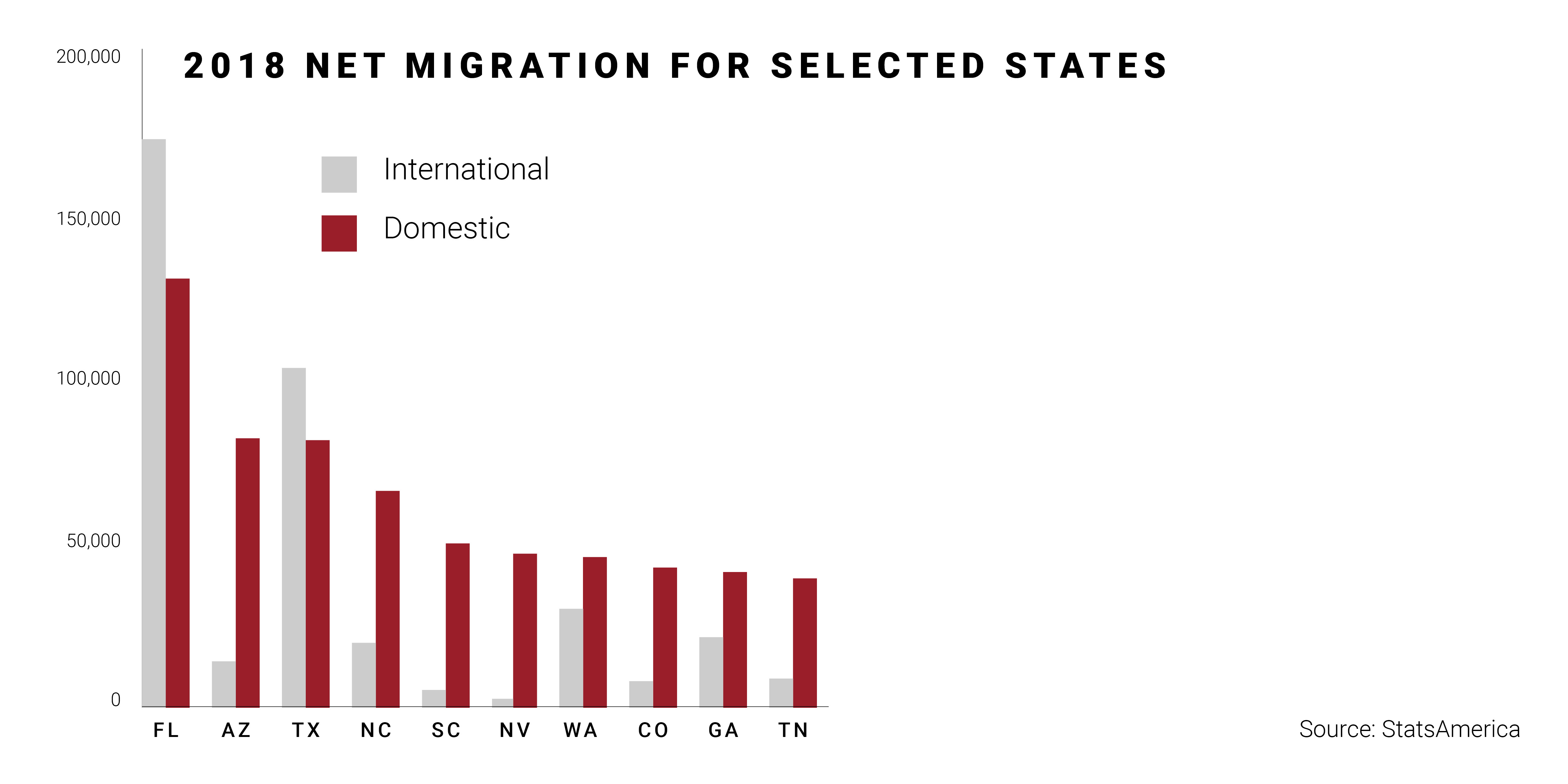

Moret: When you look at the country overall, the higher educational attainment a person has, the higher their propensity to complete an interstate move, usually for a job opportunity. Sometimes for better, affordable housing arrangements, and so forth. The Northeastern U.S. is the biggest donor region in terms of producing far more college graduates than they’re actually able to retain.

On the other hand, I forget how you describe the geography, but, basically, Texas and some of the surrounding areas are the biggest recipients of that. It’s been a few years since I’ve looked at this, but for all the new college-level jobs they have in Texas every year, they only produce about 70% of what they need and they get the rest for free from all the other states.

Kotkin: In the case of Texas, they get all the southern states, like Louisiana. Why don’t we just put up a sign that says, “Do not go to a bar in Houston when LSU is playing,” because of the number of LSU graduates you run into.

The same thing’s true with the universities of Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma. They send their kids to Texas. This is like the California I moved to in 1971, where everybody was from someplace else and nobody ever thought about leaving.

Moret: It’s kind of flipped a little bit.

Kotkin: It’s flipped quite a bit. Now, if you don’t have money, you don’t have rich parents, you didn’t rob a bank, and you’re under the age of 40, you’re in trouble.

Moret: When I was reading some reviews of “The Human City,” which were largely very positive, one that stuck with me was in The Wall Street Journal. It said, “'The Human City' does provide a vision for legitimate and pragmatic urbanism that could and should become mainstream. Indeed, at the end of the book, Mr. Kotkin seeks a constructive compromise with the anti-sprawl armies. His answer to ‘How should we live?’ is amid an ‘urban pluralism’ that encompasses the city center, as well as closed in suburbs, new fringe developments, and exurbs.”

Those who aren’t as familiar with your work tend to think of you as America’s champion for suburbs, and you are in a way. But I think what they miss is that you’re not really an anti-city or even an anti-density person. It’s more that you’re essentially making the case that when we really consider the full range of family styles and different levels of income, we need to have a diverse array of housing and neighborhood-type environments, from high-density to suburban, and others as well.

Kotkin: In Houston, the young professional wants to live where the spouse-hunting is good and the food is good, where it’s a little bit hipper. But then when they get married and want to buy a house, that same person and their spouse have lots of options that are affordable for them. The problem we have here in California, most particularly in the Bay Area — but it’s happening in other places, too — is once you’ve gotten through the 20-something phase, there’s no place to go.

If you look at the new surveys from Joint Venture Silicon Valley, 45% of all workers in their late 20s and early 30s plan on leaving. That’s not a very healthy environment. What they’ll do is keep recycling that same group over and over again, but you can’t get somebody who’s going to be there for 10, 15, 20 years. The kinds of companies that leave places like California or New York are the companies that generally need somebody for the longer term. But if you’re just using 20-somethings, they’re like cannon fodder in the First World War.

Moret: You make a mistake if you design the whole solution around that one demographic, because their desires will change over time.

Kotkin: What you’ll see, even in the current circumstances, many of these companies, if they need mature management, will move more of their operations to more affordable cities. I think Apple’s new campus in Williamson County, outside of Austin, is about half the size of the spaceship in Cupertino.

We see this here in Southern California, which, in my opinion, naturally, is the nicest urban place in the world to live. But the CEO who lives in Newport Beach is probably tempted to stay here. As one of them said to me, “Yeah, but my production workers... if I pay them $18 an hour in Dallas or Oklahoma City, they can live a decent life. Here, they’re homeless. Literally homeless.”

Moret: One of the things you wrote about in “The Human City” was how so many of the big engineering firms that had been in California have largely moved to Virginia and Texas over the years. Jacobs, Parsons, and others.

Kotkin: The loss of this kind of company, as well as the McKessons, the Toyotas, and the Nissans, meant loss of anchors in their communities. People worked there for 20, 30 years, a lot of them making $80,000 to $150,000 a year. They had some degree of stability.

In my opinion, the Nissans and Toyotas should all be in Southern California. We’re the car design capital of the world. We have big Asian communities that have been here for a long time. We’re the biggest port where the stuff gets shipped in. We’re the biggest market. But they’re moving to Tennessee and Texas for reasons that we didn’t have to have. What’s shocking to me is how little concern there is on the part of the California government about these companies leaving. When Toyota left, it was like nobody even paid attention.

Then you get economic development officials saying, “Well, we’re at this higher stage of development. We don’t need those kinds of things. Those things are all going to leave us.”

Moret: We’ll just be all tech, basically.

Kotkin: And we’ll all be a bunch of IPOs and a bunch of 30-year-old obnoxious rich kids running around. I don’t think you can base an economy on that.

Moret: Before we leave “The Human City,” what would you say readers should take as the top two or three lessons from that book?

Kotkin: The first thing is what you mentioned about the idea of urban pluralism. You have to be able to give people lots of options. So, there has to be single-family neighborhoods. There has to be higher-density, downtown development. I think in most places that’s now well overbuilt, but certainly you want to have that. And you want to have maybe that middle. I’ll give you a good example: North Austin.

The Domain is a mini-city in the north part of Austin. It has hotels, it has apartments. You could walk everywhere. It’s surrounded by single-family communities. People who live in those drive into The Domain when they want restaurants, shops, shows, whatever. Very much like The Woodlands. The Woodlands serves as the metropolitan center for a huge part of western Houston.

These have been successful. Reston has been a success story. These areas are somewhat urban, somewhat suburban. The problem you now have is planners waiting to wipe out all the single-family houses. If you want to recruit people who are now being told that their area is no longer zoned single-family because the state of California’s decided that you can build a fourplex next door, that’s the most serious discussion we’ve ever had about leaving.

Moret: In the latest Chief Executive magazine, we were happy to see Virginia moving up as one of the best states for business, but you wrote a piece in it entitled, “After Amazon: What Happened in New York Isn’t Just About New York,” that touched on some of these themes.

I’m just going to read this passage toward the end: “This suggests a surprising future for the tech economy, particularly if the progressive tide continues to mount. An aging millennial population, growing dysfunction in centers like San Francisco, and political radicalism all work against business investment and the migration of educated middle-aged adults to cities. The bad old days of urban decline may not return, but the bright high-tech future predicted for our urban cores may be far less promising than widely heralded.”

You essentially make the case that high-cost tech hubs like the Bay Area or New York City may continue to be strong, but that over time we may see a more broadly shared set of metros that attract the tech jobs. We’re already seeing that to a large extent, in part because talented professionals eventually want to seek affordable housing where they can raise a family.

By the way, I’ve seen this in my own life. My wife and I have considered moving to the Bay Area on two different occasions. We’re well-educated, lots of good options, but even with that and even with great job opportunities, the cost is just incredible. With all these things in mind, what do you think that secondary tech markets — not small metros, but let’s say the midsize metros that are experiencing growth in tech or that want to — what can they do to position themselves to participate more broadly?

Kotkin: The first thing is to understand the typology. San Francisco, the Bay Area, the Seattle area, and, to a lesser extent, Boston, are just in a completely different phase than New York. New York’s tech location quotient is just about the national average.

Moret: It’s big in an absolute sense, but not a high concentration.

Kotkin: Same thing is true with Los Angeles, which used to be the largest concentration of scientists and engineers in the world when I wrote my first book.

Then you have where the growth is going. There’s still Silicon Valley and Seattle. They’ve got the big companies, the capital networks. More private in Seattle, more venture in Northern California. But basically you’ve got places like Orlando, Raleigh, Nashville. If you look at where the biggest growth is, if you look at the location quotient numbers in the computer-related and other high-end fields, that’s where it’s going. In the case of finance, lots of movement to Florida. I think what you’re seeing is that these secondary markets have the schools, the quality of life, and the cost.

Moret: We’ve talked mostly about metro areas, the dense urban core, the largely suburban, connected localities but still in the metro area. What about regions that are predominantly rural? They’re largely experiencing decline. Certainly of population, often of employment as well. What can they be doing to position themselves for growth?

Kotkin: Not every rural area, like every city, is the same. There seem to be several types of rural areas that are growing. Characteristics vary. They could be, let’s say, Midland to Odessa. Obviously, it’s energy.

Moret: Sometimes there’s a major successful local employer.

Kotkin: Like in Lubbock, it’s Texas Tech, really a driver. In other places it’s an amenity-based economy. Like Missoula, Mont., where people with skills are moving, even though their businesses may be located in the metropolis. They live there and use the internet. There’s clearly a bit of a demographic recovery, certainly in the micropolitan areas and, to a lesser extent, in the really rural areas.

I think what’s going to happen in rural America if I were to project it, and I’ve been looking at this for 30 years, is you’re going to see some of these small towns die and some will really do well. When I looked at western Iowa, in particular, some communities were growing and looking really good. They usually had a hospital or a community college, maybe one really good employer, and they were doing fine. But if you went to the places far from the interstate, they didn’t have any plane service, no hospital, no community college. Those places have a harder time.

You have to be able to give people lots of options. So there has to be single-family neighborhoods. There has to be higher-density, downtown development.

The other thing you’re going to see is growth in exurbia. In other words, the fringes of the metros. That’s where the most rapid growth takes place now. Like in Des Moines, which is a very successful Midwest community. I asked the builders, “Where are people going?” They’re moving out to rural towns, 20 miles from Des Moines. Twenty miles in Des Moines means 20 minutes.

Twenty miles here in California could be a lifetime. So, they’re moving into these towns. It’s the same thing I saw in Fargo. People moving to these little rural towns, 10, 15 miles away, which have a town square, good schools, and very coherent communities.

On the other hand — and this is another aspect of this — when I first started going to Fargo about 20, 25 years ago, downtown was a pit. There was nothing. It was crappy hotels and crappy restaurants and no street scene at all. Right now, Fargo has a wonderful boutique hotel, really good restaurants, ethnic diversity.

My friend Shaheen Sadeghi develops what he calls anti-malls — malls that are all just locally owned businesses. He said, “Every place is cool now.” If you want your avocado toast, you can get it pretty much anywhere. It used to be if you wanted a good cup of coffee, when you left New York, you didn’t get a good cup of coffee until you got to San Francisco. I’m not talking about Starbucks. Now, you can get a good cup of locally brewed coffee in almost every major city. Fargo has quite a few really good coffee shops.

Moret: How important is broadband access to rural development?

Kotkin: The internet is a potential game-changer. When I first started working in that part of the country, in the Great Plains, it was really funny. You’d get a three-day-old newspaper that was all dog-eared. If you wanted to watch television, there’d be two stations and it was blurry.

Now, you can go to a rural community and get The Wall Street Journal online at the same time as the guy in New York gets it. And you have cable television. You can get the same crap there that you get here. I think that those cultural differences are less.

Now, when you’re young, and particularly if you’re from an affluent background, you still want the New Yorks and the L.A.s, the San Franciscos and Chicagos. But as you get older, how often do you go to the jazz club? Friends in North Dakota say, “The Rolling Stones give concerts in Fargo.” In other words, the spread of popular culture has changed enormously. So, places you would have never thought of going to, you now go to.

Moret: Joel, thanks again for making time to visit. It was great to catch up over breakfast. Thank you so much for being with us today.

Kotkin: Oh, thank you.

For the full interview, visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts