Beyond One-Size-Fits-All College Dreams

A Conversation With James Rosenbaum

James Rosenbaum is a professor of human development, social policy, and sociology at Northwestern University’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and a faculty fellow at the Institute for Policy Research. He specializes in research on work, education, and housing opportunities. His books include “Bridging the Gaps: College Pathways to Career Success” and “After Admission: From College Access to College Success.” VEDP President and CEO Stephen Moret sat down with him to discuss how the traditional college model fails some students and what can be done to make it work better.

Stephen Moret: You recently published a book with a couple of co-authors called “Bridging the Gaps: College Pathways to Career Success.” And in that book, you talk about three gaps: students taking courses without getting credits, students getting credits that didn’t count for credentials, and then getting credentials that don’t have payoffs in the labor market.

James Rosenbaum: The focus on gaps is important because we designed a higher education system for a certain group of students. We all know what college is. It’s the experience that we had, and that is in a traditional college with traditional procedures. Fortunately, we have expanded opportunities for college now to nearly everybody. It is astounding to see in the cohort of students we studied. They were seniors in 2004, and we looked at what happened to them over the next eight years. Ninety percent of high school graduates go to college. They won’t go at once — the usual statistic is about two-thirds. But over the next few years, many more students realize, “I don’t have a chance unless I go to college,” and they change their mind. They raise their expectations, and they go to college. The problem is, college has not been well designed for many of these students, and that leads to the gaps that you just mentioned.

Moret: Particularly the non-traditional sort of cohorts.

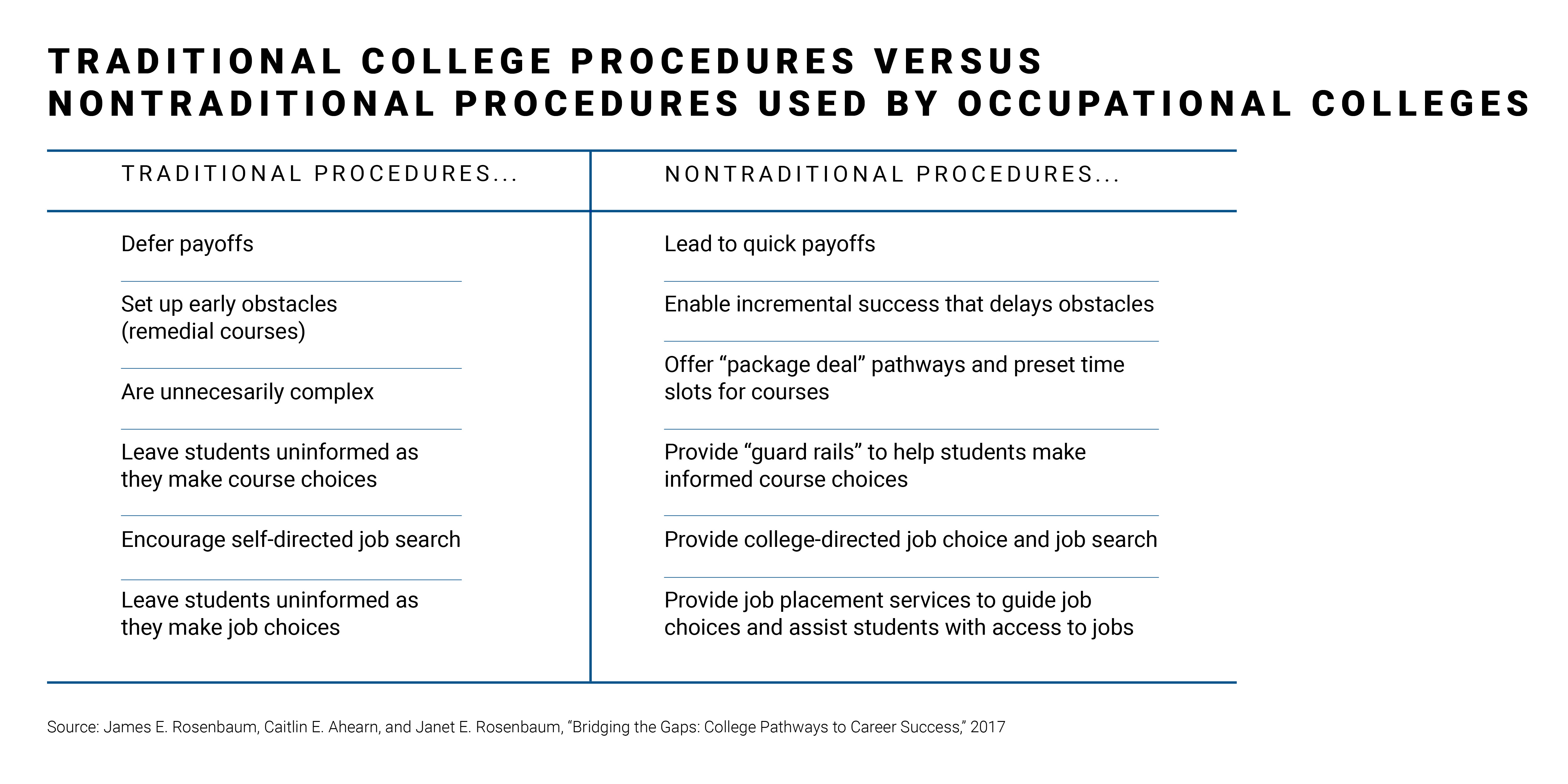

Rosenbaum: That’s exactly right. We have students who are motivated to go to college, and they could benefit from certain kinds of college, but we give them a one-size-fits-all model, and that doesn’t work very well for many students. And so we end up with students basically facing each of those gaps. Some of the gaps are of our own construction, where we have created a system which looked fine by our traditional criteria, but when matched against the new students, it doesn’t work. And so, in essence, what’s useful about this perception about gaps is: We created them, we can un-create them, and we can actually see the ways to address the problems that we face.

And here, the problems are very serious. Community college is wonderful. It creates open access at very low cost and meets labor market demands. But community colleges have very poor rates of completion of any credential. And if you don’t complete a credential, you don’t get a payoff, and so we need to be able to rethink what we are doing here. What kind of college is going to be beneficial to the new kinds of students? There’s a lot that can be beneficial, and it turns out it’s worth more than we thought — what we call sub-baccalaureate credentials: certificates and associate degrees. They have lower average earnings, and that’s well known. What’s not known is, the overlap of earnings with B.A.’s is enormously strong. The top 25% of people with a one-year certificate earn more than most B.A.’s earn — and on the other end, a very comparable figure, the bottom 25% of B.A.’s earn less than most certificate holders earn. And the findings are even stronger for associate degrees.

Moret: There are some reasons why these gaps occur. I suppose a lot of it, as you mentioned, is that we’ve focused on these traditional college students, and have perhaps not redesigned the system, or at least created pathways in the system sufficient to support those non-traditional students. But why do you think it’s taking so long for the United States to be able to shift toward a model that would better serve the broad array of students that higher education serves in this country?

Rosenbaum: I think one of the ironic features of the American system is: We are very idealistic, and we’re accomplishing a lot of our ideals. And so when I say 90% of high school graduates are going to college, think about your high school class and the diversity of interests and the diversity of skills in that. We are succeeding beyond anything I thought was possible in terms of getting people into college, and that’s a success that creates its own problems. And so part of our problem is just that. The other part is — and this is not a good thing — we often blame students for their failures, and often the deck is stacked against them. We need to do a better job of understanding: To what extent are we putting people in a situation where they can’t win? And to what extent are there other options that are not usually thought of where they can win?

I think we’ve got some of the pieces in place, but we don’t have the advice in place. We don’t have the advising procedure in place. We totally skimp on investing in counselors and advisors and giving them the information they need to give good advice.

Moret: You mentioned the issue with counselors. As I look at the research that’s been done about higher education and the labor market, one of the most common broadly shared recommendations to make the system work better is to improve the availability and the quality of advising and coaching, both in K-12 and in college, and yet we don’t seem to be making much progress in that direction. There’s some evidence that quite a bit of institutions are actually going the other direction. What has to happen to make some real progress in that area?

Rosenbaum: Well, there’s one thing that is well-known, and it’s very much true: The student caseload for counselors is abysmal. In high schools, it’s not good — 300 students to one counselor. In community colleges, it’s horrid — 1,000 students to one counselor. And that’s a low-ball number. There are many cases I know of 2,000, 3,000, or more. We do not have a counseling system in the community colleges, basically.

But the other piece is something we can do without very much cost. And that is: Devise systematic advice that we can give to students about what their options are, the advantages of those options, who they work particularly well for, and who they don’t work for, giving realistic advice in a systematic way. And here the kind of thing that researchers do, I think, can be very helpful, because researchers look at what actually happens. They don’t just look at what the goals are — they look at what actual outcomes are.

Moret: You also talk about something where there’s a lot of economies of scale with having just the information base. You could almost imagine a technology solution there. Who has gotten closest to creating something like this that’s accessible to prospective college students?

Rosenbaum: Part of it is software. Naviance’s software and other brands of college readiness software are often very useful for advising students about which colleges to apply to. And that kind of matching of students’ background achievement, programs of study, interests, geographical preferences, can be inputted into the software, and advice can be given. Unfortunately, that doesn’t go far enough, and we really need to be developing software, and actually even sheets of paper, that would guide counselors to respond to students whose achievement is much below the usual average traditional college entrance achievement. And the alternative interests — the love of doing technical things, working with electronics, working with mechanical things — these kinds of alternatives aren’t in the software that I know of, and yet they’re important for people’s choices.

We’ve gotten to a place where we’re admitting students, new kinds of students, and we haven’t gotten to the place where we can tell them where they can benefit, and where they can actually have their own interests and own abilities recognized.

Moret: The data sets that are currently available often talk about, “Well, here’s all the jobs and what they pay, and what the required education is,” let’s say, but there’s not enough of a sense of how you navigate from where you are today to these outcomes.

Rosenbaum: It’s absolutely a missing link, and it is a crucial link. Students want advice about these things. They want someone who knows them even a little bit, who can make a judgment about what’s an appropriate set of goals, what are alternative goals, and to work that through. And so students need that kind of advice. The Bureau of Labor Statistics book — I don’t know if it’s still down on paper, but when it was down on paper, it was four inches thick of listing just jobs and aspects of jobs. And it’s overwhelming in a way that students can’t possibly cope with. We need to find ways to target more clearly and make those targets consistent with the local labor market.

Moret: I don’t know if you saw there was a recent piece that essentially made the case for a new learning ecosystem. And one of the key features of that, they called navigation. And it was this whole idea about helping individuals to assess where they are today, to understand the options available to them, and the different pathways to get there. And I certainly agree with you — the opportunity for a technology-enabled solution seems like a big part of it.

Rosenbaum: One of the counterparts of this is the college system, where we offer an overwhelming number of options for students to take without very much guidance. The gaps that you were mentioning earlier, many of them come from students making suboptimal choices that they couldn’t anticipate.

One of the recommendations that I’ve made in the past, and it’s now being adopted quite generally, is creating guided pathways. And these pathways are sought among the thousands of courses you can take, and say, “If you want this goal, here are the things you should do to achieve it. And this is when you should take this course. Taking them out of sequence often doesn’t work, and doesn’t give you credit, and leads to failure.” So regimenting the curriculum in a way that makes it clear: You choose your goal, ideally with some help from a counselor or advisor, and then the college will provide all of the steps in the right order that you need to get there.

Moret: In your most recent book, you talk a bit about the College Scorecard, and perhaps some benefits of it, but also some shortcomings of it. I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to peruse the new version, but in the last few months, a new version has come out. I’d be curious about what you see as the benefits of how it’s evolved, but also, could you elaborate a little bit on what you think could be done to improve it?

One of the things, for example, you talked about — earnings is certainly one relevant outcome, but there’s also non-monetary benefits of education and work that perhaps could be incorporated in some way.

Rosenbaum: The College Scorecard looks at easily measured features, and that comes out to getting a job, maybe getting a job in the right area, and earnings. And there’s much more that is important, especially in the early career. When you first start, we’ll often think, “Well, you want to get better earnings.” Turns out that’s often the wrong answer, that it’s better to choose to consider the tradeoff between earnings and getting training — get experiences that are going to be valued. Students complain sometimes that the college aims them at lower earnings than they could get on their own. But the jobs they find on their own don’t give them relevant job experience and are going to be a dead end for their career.

College staff often actually know what are the good training experiences students could get in their first jobs that are going to lead to a much more successful career later. Aiming too much for high earnings in that first job can be a problem. I think the Scorecard is well-intentioned, and to some degree, can be used cautiously. But it’s not the whole story, and if followed too rigorously, particularly with high-stakes punishments, it could do damage.

Moret: As you rightly pointed out, there’s a huge distribution in the employment outcomes that individuals have. One of the areas of study that I think is getting a little bit more attention lately is the underemployment problem. We have historically low unemployment,

but underemployment, even of bachelor’s grads, is quite material in the U.S. Some estimates are order of magnitude, 30% or so, of full-time employed adults in the U.S. with a bachelor’s degree or higher not working in a college-level occupation.

What do you think about the research in that area right now, and is there anything that you’ve gleaned about what you think could be done to kind of improve on that situation?

We need to do a better job of understanding: To what extent are we putting people in a situation where they can't win? And to what extent are there other options that are not usually thought of where they can win?

Rosenbaum: It’s a great question and very important. We have looked at the B.A. degree as offering a good education, but also, it’s offering high status. And we do that based on averages as if everybody was at an average. And there’s wide variation within the earnings of B.A.’s and in the earnings of other degrees as well, and it turns out that there’s an enormous overlap between these. So if we were just going on earnings, we would come to the conclusion that, mostly, it’s a big overlap. And students who choose a B.A. are often not going to have higher earnings than someone with an associate degree, even though they’re spending many more years getting it.

And usually, if you take longer than four years to get your B.A., those last years are ones that you didn’t expect to have to be paying for. So there are a lot of problems with a B.A. that we are not very candid about, and as a result, students are caught shorthanded with not enough money, and not enough time, and promises they made to family, and promises they made to employers about how many years college would constrain their hours.

The underemployment also relates to field of study. Students with a B.A. come from various majors, and those majors change the outcomes enormously. And so, a major in a STEM field, everybody knows there’s great value in that. The average monetary value of a bachelor’s degree in English, or a bachelor’s degree in some other liberal arts field, may not be as great.

And this question of variation turns out to be especially important, actually, here. But more important than earnings is: What’s the future trajectory, and to what extent are students going to be getting a good career that’s going to have a future? And students often don’t understand that, and advisors are not very good about telling them, “It is crucial that you make a decision of getting a job that’s going to have a future for you.”

Moret: It gets back to helping people think about the choices that they make, and how they impact a future economic opportunity, if you will. Some other countries do perhaps a better job at this than we do. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Rosenbaum: Well, Germany certainly comes to mind. Germany has a total belief that young people can do a lot of things that we think they can’t do. And in Steve Hamilton’s study of German apprenticeships, he found 18-year-olds who are not college educated doing clerical-type jobs of considerable responsibility. And he said, “We don’t think 18-year-olds can do that kind of thing in this country.” And so we sell short the students, we sell short the experiences they get, we underutilize them, and we under-train them. And so the German apprenticeship experience is one that tells us we could be doing a lot more, and it does require investment. Partly from employers, perhaps from the government, but somebody needs to make these investments. Because without these initial investments, we basically lose a lot of capability that we could have otherwise.

In Japan, there is a strong linkage between work and high school, and graduating students are recommended for certain jobs based upon their hard work and achievements in high school.

Moret: In high school? Interesting.

Rosenbaum: And these were direct linkages, direct relationships, where a local employer would say, “Well, we’ll give you 20 slots. You nominate 20 people that you think are going to do a good job. Don’t recommend someone who’s not going to do a good job, because then we’ll not come back with job openings next year.”

I think we've got some of the pieces in place, but we don't have the advice in place. We don't have the advising procedure in place. We totally skimp on investing in counselors and advisors and in giving them the information they need to give good advice.

Moret: Who’s doing the recommending?

Rosenbaum: The high school counselor evaluates the students based largely on their grades, and says, “These are the students we think will work hard and can do a good job.” But they won’t fill out their quota of 20 jobs with 20 people, if they don’t think they can handle it, because they don’t want to disappoint the employer.

Moret: Why don’t we do that in the U.S.?

Rosenbaum: I don’t know why we don’t do it. We come closer to doing it for college graduates, but we still don’t do it. It’s such a missing link, because work-bound students don’t have incentives for getting good grades, employers don’t get valuable indicators of student work habits, and teachers give grades and ratings that students ignore and don’t work for. Instead, we create competition among students on artificial criteria that don’t matter. They compete on grades. They compete on number of activities. You see these really amazing résumés, but none of it tells us anything we want to know, what employers want to know, because they want to know about soft skills, they want to know about persistence, they want to know about attention to quality, they want to know about problem-solving. None of those are in the résumé. All of those are things that faculty could make recommendations about students, and we don’t have a trusted linkage between teachers and employers, so we can’t convey that information.

What’s needed is a trusted relationship where the school says, “We like having this kind of relationship. We will treat it seriously. We will give grades and candid recommendations,” and employers will get valuable information, will hire students who work hard, and will come back to us next year.

Moret: One of our great ambitions in Virginia is, we really aspire to be the state that is the best in the country at this topic. Essentially at the whole range of things we might put under the label of human capital development. And part of that is helping improve these connections, helping people to better navigate the opportunities available to them, and to pursue those. You articulate some fabulous ideas, not only in your most recent book, but in some of your past writing. Some of those have already been implemented in some places, and others are promising, based on research today. Do you think colleges, states, and/or the federal government need to craft new structures to better enable these things to happen?

It seems to me there’s so many of these great ideas that just perhaps don’t have a champion to really make them happen. And I wonder if part of the answer is some kind of structural shift.

Rosenbaum: I think that’s exactly right. And that’s perhaps a weak point of the American system. We mistrust structure, we mistrust big government and big programs, and we love decentralization, we love individual initiative, and that’s not going to be enough. This is a big problem, and we have big things to do. One of the biggest is alignment. We have very poor alignment between K-8 and high school, between high school and college, between two-year colleges and four-year colleges, and then between colleges and work. Without alignment, we’re at cross purposes.

And so we have high school exit exams, a wonderful idea for measuring the accomplishments of students. Unfortunately, students will pass the high school exit exam, and three months later show up at a college where they fail the remedial placement exam. That’s poor interaction and alignment. And I wrote a piece recommending that we do alignment. Harper College in Illinois has actually done that.

Moret: Really?

Rosenbaum: The provost at Harper College, Judith Marwick, created an alignment system where the college remedial placement exam is given in 11th grade. All of a sudden, students got information about how prepared they are for college. And if students fail, that’s great, that doesn’t matter, because they’ve got a whole year to work on it. And that’s what they do. They devote senior year to remedying the problems that students have, and they’re easily identified by this procedure. This alignment means that many more students enter college ready to do college-level work.

It also says, “We’ve got this missed opportunity. We’ve got the high school trying to prepare students, we just don’t have the right standards and curriculum in place.” This kind of alignment does that. Now you can do the same story for the next leap. The alignment between community college and four-year college is very poor. Four-year colleges allow students to transfer in, and they make it very difficult to get to actually do that. And inevitably, students have taken many courses which don’t match the courses that the four-year college expects.

And even in the state of Illinois, where we have an articulation agreement, that only covers electives. It doesn’t cover the major. And so here we’ve got this act that was intended to make everything count, it doesn’t count for the major. General Ed may count, but your economics major, your economic courses, may not count at all. And it’s hard to anticipate that. At one four-year college, actually, the guy who is in charge of deciding which credits counted said his job was to give people the bad news that much of what they’ve got doesn’t count. And he said, “Maybe instead of that, I should be talking to entering community college students and telling them what they can take at that college that’s going to count at our college.” And so, basically, he’s turned his job into advising students that he didn’t even have yet. That kind of effort is rare. The misalignment we usually find is just inexcusable, and it’s easily fixed, but it is rarely fixed, and we need to do more to make that alignment work.

Moret: Was there anything else that you wanted to share that you think we should have touched on that perhaps we didn’t?

Rosenbaum: One thing that I am struck by is, we talk about the choice of degree as if it’s an either/or.

Moret: You need a B.A. or less than B.A. — is that what you mean?

Rosenbaum: Yes, B.A. or an associate degree, or a certificate. It’s not either/or. You can do both/and. And I think we need more strategies where students will not just choose a goal, but they’ll choose how to get to that goal. They may choose a B.A., but do it by first getting a certificate, then getting an associate degree, then getting the B.A. It may take a little longer, but it provides payoffs all the way along.

Moret: Off-ramps at every stage, basically.

Rosenbaum: That’s right. Students who have high risk of college being interrupted, students who have high risk of finding the courses too difficult, will get something along the way, even if they don’t get all the way to the B.A. And it means that they have payoffs right away. It means they have better earnings to support their college careers. It means that they’re getting a set of expertise that is valued from the very beginning. And we don’t do enough of that. It seems to me that incremental success is a great way to hedge your bets, and a great way to get payoffs, and to be able to leverage your job experiences with your training.

Moret: It’s a wonderful idea. I want to thank you so much for taking time to visit with us today, and especially for the really outstanding and important work that you’ve done and that you continue to do. We’ve benefited from it in Virginia, I’ve benefited from it in my own career, and I’m looking forward to staying in touch in the years ahead.

Rosenbaum: Thank you. I enjoyed it also, Stephen.

For the full interview, visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts