What's Next for the Food & Beverage Industry?

A Conversation With Brian Corde, Scott Kupperman, and Brandon Talbert

Food and beverage processors operate in an industry where even the most successful companies depend on low margins and economies of scale. That means even the smallest advantage can be a differentiating factor when locating a new facility. VEDP President and CEO Stephen Moret spoke with three leading site consultants on the factors that make states and localities successful in attracting food and beverage projects.

Stephen Moret: As you think about what you’re seeing in the food and beverage industry with your clients as well as what you see in the sector more broadly, what are you seeing out there as the major trends that will affect company operations and location decisions over the next few years in food and beverage specifically?

Brian Corde: I think the changes that we’ve seen over the last couple of years have really formulated the trend that I think will continue over the next few years, and that is a lot of shifting in customer choice — a lot of what I’ll call lifestyle brands of companies popping up with products. And in addition to that, there’s been a very key consideration by companies to shorten their distribution model, not only from the standpoint of getting a product to customers in certain key areas, but then also the proximity of their manufacturing locations to their raw materials as consumers are forcing the change to fresher ingredients and more availability of those ingredients. We’re seeing a major shift in the thought process on location of the manufacturing operations as well as the distribution networks, and I would expect that to continue.

Scott Kupperman: There are three kinds of general factors that I would say are common to what almost every project I’m working on is looking for. One is because the margins in this industry are terrible — low-cost locations, especially on the production side, are really becoming areas of focus, and any place that can offer very competitive costs relative to real estate, labor, utilities, and more generosity on the incentive side definitely should have an advantage.

The second thing is that almost any food and beverage company is obsessed with risk — both the risks associated with the time, costs, and resources required to get a new facility operational, finding a new location, and putting a facility in place, and certainly with the risk associated with operating it both in a safe and regulatory-compliant status. There’s been plenty of stories out there about companies that haven’t, and the damage done to those businesses can be tremendous.

And then lastly, companies in the food and beverage industry right now are living and dying on their ability to put new ideas into production quickly, which is really what they call innovation. They’ve got to be incredibly nimble and responsive to consumer trends and demands and be able to change what they do in every regard very quickly. I always encourage people in economic development to think out of the box and tell a story about what resources their community has that can contribute to that need to innovate.

Brandon Talbert: I think we’re seeing an unprecedented level of innovation in the food and beverage industry. There are a few different reasons. One is the culinary bar has been raised here in the United States. People become exposed to new foods and there’s more of a willingness to try new things and to prepare new foods, so we see that trickle down into the manufacturing sector with a number of different factors that are driving that — everything from dietary preferences to allergies and just consumer awareness of what they’re consuming, more attention to the ingredients and clean-label products. And you’re seeing manufacturers have to respond very quickly to that. There’s an increased level of focus on efficiency and being very cost-conscious, not only with transportation costs, but all operating costs.

Moret: As you think about some of the site searches you’ve done recently and others that you’re anticipating doing, what are the main location criteria that companies are thinking about and how are they prioritizing those things?

Talbert: I’d say number one is labor. We’ve seen clients that have had to really take a close look at their wages and benefits. In this market, the competition has been a challenge for many food companies, and I think companies have responded to that by trying to improve their wages, but also control their wages when looking at new locations. Not only that, but being able to find and being able to locate in places where they can ensure that they have an adequate labor force to support the project. A lot of companies in the industry have struggled with that. That’s probably the biggest point of sensitivity for most companies when selecting a location.

There's been a very key consideration by companies to shorten their distribution model, not only from the standpoint of getting a product to customers in certain key areas, but then also the proximity of their manufacturing locations to their raw materials as consumers are forcing the change to fresher ingredients and more availability of those ingredients.

Kupperman: More than ever, on a case-by-case basis, the mix of priorities changes from company to company, and sometimes from the same company year to year. And that’s always among the most critical parts of a project — working with your client to get their priorities straight. Labor, real estate, and time to deliver the facility and the project are all critical factors. But more and more, I think it depends on whether or not the company has an outward-facing consumer brand that they want to protect and uphold and try to find an overall solution that can contribute to that.

Moret: With those location criteria in mind, obviously you guys have traveled across the country quite a bit. You’ve met with regional groups, state groups, local groups. As you think about the range of experiences that you’ve had across the country, what do you think states and regions can do to better position themselves to attract the food and beverage industry in particular?

Kupperman: I always tell economic developers, “If you’re going to focus on this or any other target industry, you’ve got to tell a story. And do more than just put a load of data together and dump it in front of us.” I think especially in this industry, the basis of a compelling argument is to say, “We’ve got and can demonstrate a successful history of companies in the food and beverage industry already being here,” and “There’s all different types of manufacturing going on here and we want to show you that we have the capacity for more. More as it relates to real estate, labor, and community resources that support a successful startup and stabilized operation.” You’ve got to put together a compelling story that demonstrates what availability you have and what skills are present and what training you have to further develop that market.

Food and beverage companies do not like pioneering and being the first going into an area where it’s been predominantly pharma or auto or textiles. They like going into a place knowing that they can minimize their risk by having resources already there to support their type of industry. If those factors are prevalent in your community, I think that’s a way to frame your argument to attract more.

Corde: I think that we’re seeing quite a bit of a desire for the clustering effect to take place. Demonstrating that there is a critical mass of professionals there that have a familiarity with this type of industry is really critical to achieving that success. In addition to that, I think if you’re thinking outside the box, the area that I think would be really important to focus in on is the complete supply chain analysis for a company. So it’s not just about the easy ones. Where are your customers? Where are your raw materials? While those are extremely important, it’s also about how much opportunity is there for your entire process.

Is the packaging of those products readily available? Can we get bottling done, or can we get Tetra Pak products in there easily? And then in addition to that, there are opportunities for identification of logistical advantages. We know how critical logistics are as part of the food manufacturing supply chain. If there’s rail access and somebody that’s been producing a product, particularly by bringing in their raw materials via a truck before, but now you have the opportunity to bring in via rail, those can be significant game changers for those types of operations.

Talbert: There’s less perceived risk when you’re going into a community or region that has demonstrated that other food and beverage companies are operating successfully there — that they’re finding the people they need, that they’re able to find the utility capacity, particularly with some of the demands on certain food and beverage processes around water and wastewater that can be significant. That there’s a friendly operating environment and from a transportation standpoint, being able to benefit from areas that have a good supply of trucks and particularly with companies that ship a lot of their product in refrigerated trucks, access to those lanes can be a real advantage for locating nearby.

And in areas that don’t have other food plants, we’ve also seen some companies find success when you see an opportunity to differentiate yourself from other employers in the market. But I think the critical thing is that the community, the region, and the state had a supportive environment. They’ve demonstrated that they understand what it takes to support these kinds of industry and they’ve expressed interest in locating there, and that sends a positive message to companies that are really interested in these kinds of plants and in establishing a good relationship with the community long-term.

Moret: Are there infrastructure investments that could be made by a locality or state to help position an area to attract the food and beverage processing industry? Sometimes there are certain types of wastewater system parameters that could be helpful for some operations, for example.

Corde: That’s exactly where I would start, because I think those are the two biggest infrastructure needs that the community would have. Water and wastewater capacity are two critical elements of infrastructure that are definitely needed. There’s also a challenge right now with the availability of existing buildings. There just doesn’t seem to be a great amount of inventory in that space. And that can be a challenge. If you count that as an infrastructure item, having buildings that can be repurposed but that have the infrastructure that’s required already. And that could be electrical capacity and, again, water and wastewater capacity. Those are all, I think, critical components of infrastructure improvements that can be made to help ease the burden on the companies that are out there looking for new sites.

Kupperman: The answer is going to depend on, really, how much they want to invest. At the first level, having a handful of sites that have complete access and full utility infrastructure in place to the property perimeter. Certainly, including a pretty robust wastewater treatment system, public gas, public water and sewer, and enough power for a reasonably sized food processing project. To be able to have sites between 10 and 30 acres that really are well positioned for these types of companies would give many communities an advantage. We’re starting to see a lack of really viable near-term ready sites due to demand from a strong economy and a lack of investment in ready-to-go sites.

In the food industry in particular, if they want to take it one step further and they’re investing in real estate as an economic development tool, I would do a little bit of preliminary planning and try to create a property environment that has a significant amount of buffer around it. Many of these types of processing facilities are not going to do well in a very high-density park. Are they going to get excited about a park that has mixed uses with a potential threat of an incompatible use on the adjacent property coming up at some point in their future? Some planning to show that there’s been thought around that both from a zoning or restrictive covenant standpoint and just size, offering some extra buffer and protection would be time and effort well spent.

Talbert: I would agree we’re seeing a serious shortage of suitable properties of ready-to-go properties, in the right locations. I think with a lot of these plants, they’re so specialized and it’s often more expensive to go in and renovate an existing building that doesn’t really meet the requirements. We’re seeing the trend towards more of these projects starting with greenfield in mind. With that, having an inventory of properties that are ready to go with all the utilities available, looking at your wastewater treatment plant and not just looking at the total capacity, but really looking at, is it designed to handle large volumes of organic waste associated with many food plants, not just domestic wastewater. Really knowing what your assets are and then looking at addressing some of those infrastructure deficiencies beforehand will get you more looks.

The cost of having to invest in a pretreatment facility can be millions of dollars and it’s not something that most companies want to have to do. So I think to the point about incompatible uses, having either planning in place to address that or being willing to impose restrictions that support concerns that a company may have. Whether it’s concern over allergens or heavy metals or really heavy industry that’s incompatible with these types of plants, even if it doesn’t exist today, being receptive to making those modifications is something that many companies in this industry are looking for.

Companies in the food and beverage industry right now are living and dying on their ability to put new ideas into production quickly. They've got to be incredibly nimble and responsive to consumer trends and demands and be able to change what they do in every regard very quickly.

Moret: I know you guys have experience with the Commonwealth. What qualities do you think help position Virginia as a good location for food and beverage processing sites?

Kupperman: I recently had my fourth project land in Virginia, and two out of those four have been companies based in California who have located their second facility in Virginia. You’re really well positioned to be central to the eastern half of the U.S. You’re a right-to-work state. You’ve got good access to population centers north and south of you. One of your biggest assets is a good mix of both metropolitan areas that have low-cost blue-collar communities around them and then some really interesting and authentic smaller communities, especially in the western part of the state.

And I think companies from the West Coast or other parts of the country see value in coming to the beautiful part of your state, and communities that value a healthy, outdoor, authentic lifestyle, and community brands. I think the Shenandoah Valley has taken advantage of that. I think Roanoke, where the project I just worked on ended up, has a lot more runway and can capture more of those companies.

Talbert: From a distribution standpoint, we find ourselves looking at Virginia a lot of times for a single-plant strategy in the eastern U.S. or a single plant for a particular product line in the eastern U.S. because of your location. You’re very close to the East Coast, New York, D.C., and then from Virginia you’ve got good access to the Southeast and Midwest as well. When we run through the freight cost modeling on a lot of these types of scenarios, Virginia usually ranks very well.

Corde: Virginia is a state that has agricultural roots even going back to tobacco, and I think that plays heavily into the ability to attract and make those in the food industry feel very comfortable with the product that they’ll be able to find by locating there.

And then I certainly don’t want to downplay the importance of the water — not only the abundance of the water, but the quality of the water, too, has really set itself apart from a lot of the other areas across the country. For those that have real concerns or this is a critical part of their analysis, that water quality and water availability really will continue to drive quite a bit of looks your way.

Kupperman: Having a really solid port, for some companies, is going to be a big differentiator as well.

Moret: That’s a great point. Brian just came to visit The Port of Virginia recently. What were your impressions?

Corde: It was fantastic. In particular, the thing that’s so impressive to me is the amount of continuous investment at the port facility there. There is a real desire to continue to be a major player on the Eastern Seaboard. And in addition to that, the amount of technology that continues to be implemented in the port is just staggering to me. It’s really an amazing facility. Great asset for the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Moret: As you think about talent, what talent considerations come into play for food and beverage operations, and are there things that states and educational partners can do to build a workforce for those types of projects? I’m also curious if there are any states or programs that you might cite that have impressed you in that respect.

Talbert: It really runs the gamut. You’re seeing the skill level required from operators, technicians, increase from what it’s been historically. And the area that, not unlike other industries, many food companies really have the most difficult time staffing are the positions associated with maintaining all of the equipment. Particularly in some of these plants that are highly automated, have very expensive refrigeration equipment, having a skilled workforce and training programs to support those requirements is very important. And then at the managerial level, you see a lot of people in the food industry tend to move around. They’re pretty mobile.

Being in an area that’s attractive for folks from different parts of the country, and even world, to relocate, and having the assets in place and community housing, in terms of community appeal and the type of amenities that people are looking for, can be a real big driver — particularly for some companies that are really concerned about making sure that they’re going to be able to relocate the talent that they may not be able to find in the marketplace.

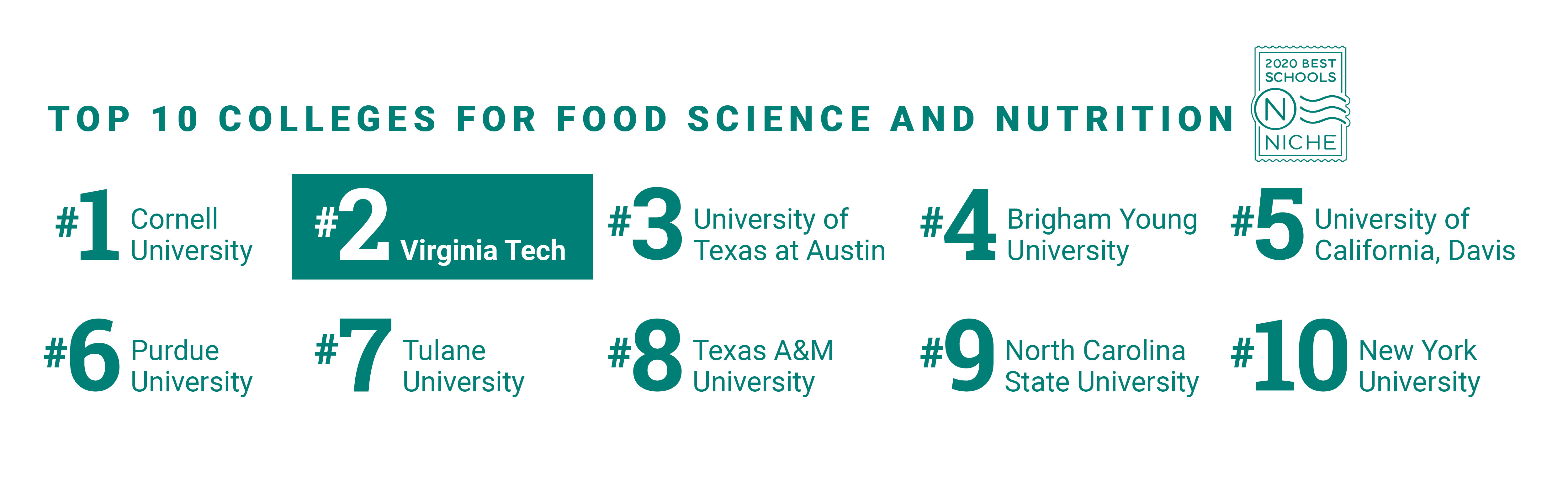

Kupperman: One of the assets that you do have is the growth of the food science program at Virginia Tech. Not all companies are going to need people with that level of expertise or degree attainment. But most projects I work on really like to know that there are programs involved both as a means of getting talent and potentially a means to test or develop some of their products within the state. And they look very favorably upon that.

And there are people at Virginia Tech who I’ve interacted with who get involved in economic development on behalf of that program and who do it extremely well, and make it very clear how companies can partner with the university to take advantage of what they have.

Corde: Anytime we’re working with a food and beverage product, I would always say that food safety is their number one concern. Training at the university level for certain positions within the facility is extremely important to assure that those safety procedures are being developed and implemented and followed.

Even down to the production workers, having those training classes that are available regarding food safety I think is one of the critical things that we see from a production workforce standpoint that these companies are really interested in. So it is a top-down training model, starting with some of your degreed folks that might be in the facility extending to the maintenance personnel and having the ability to upkeep that equipment.

Moret: Shifting gears again, you know Virginia has long been known for its wine operations, and recently we’ve seen an uptick in beer production as well over the last several years with craft beer. To the extent you guys have worked on those types of projects, what factors do you see that play into those location decisions that may be a little different than more typical food and beverage processing operation?

Kupperman: Those types of companies are all about their brand. And the few that I’ve worked with are extremely picky about where they go relative to, is there going to be some sort of energy behind their brand and that community based on who’s already there based on local demographics. Is there a flow of tourism in some way that they can piggyback on. A lot of those companies are now turning to craft cocktails and sparkling water, which are very high-growth segments in the beverage industry. It just doesn’t have to be beer. They’re going to be concerned with very similar things. Trying to further their brand and get some energy behind it based on where they are.

Talbert: A lot of companies in that segment of the beverage industry are very sensitive to brand and to cultural fit. And a lot of times that’s tied to the brand and it’s just tied to the culture of the company and the way they operate. A lot of them have connectivity to the outdoors, particularly where you see a lot of these companies started out as startups and still have that startup culture in many ways. I think there’s still a lot of room for innovation in the industry.

You see in some states, particularly in the Southeast, just antiquated alcohol laws that restrict the company’s ability to distribute within the state the way they want to distribute, and in some cases, provide access to the public. And there’s been a lot of improvements with just the recent growth in the industry. I think Virginia was at the forefront of making some of those changes that really date back to the Prohibition era and making it a much more friendly environment.

Moret: We often talk about quality of life issues. I’m curious how often you see that as an important site selection factor in the food and beverage industry.

Corde: It comes down to talent, and quality of life is extremely important these days in the ability to attract and retain talent. There are obviously perception issues about the types of jobs that are offered in a manufacturing environment. But in addition to that, it’s also the location of some of those facilities. People want to live in places that they deem to be good places to live. And a lot of times we just don’t see too many manufacturing operations or enough manufacturing operations that are located in those areas. And because of that, I do think it’s extremely important to have quality of place as you’re looking at the factors to take into consideration during a site location project — even for a manufacturing operation. Because you’re going to need to make sure that you’re going to have that critical mass of people that are going to be there to work in your facility.

At the end of the day, it doesn’t matter how cheap an area is. If you can’t get people to come to work and if you can’t get them to stay there, it’s just not going to work from a location standpoint. And so this is something that needs to be factored into the company’s model.

Moret: Was there anything else you think is important for our readers to know when it comes to this industry sector, from a site selection perspective?

Talbert: I think you can see there’s a lot of complexity that goes into the site selection process and balancing all of these factors. I think it’s important for states and regions and communities that want to attract this industry to have a good understanding of their complexity and that there’s just a targeted strategy and resources available to support this type of development, and there’s a commitment to that.

There's less perceived risk when you're going into a community or region that has demonstrated that other food and beverage companies are operating successfully there.

Kupperman: The number of economic development organizations that have reached out to me to say, “We’d like to improve the way we attract food and beverage companies to our part of the world,” has grown tremendously from all across the country in say the past two to four years. There just seems to have been a real increase in energy behind those efforts, and especially from some other states in the Mid-Atlantic, Southeast, some of your geographic neighbors. And these are not only state entities, but some of the big regional utility players — certainly, regional organizations and even smaller communities who may have had a couple of wins and want to further develop their cluster.

They say, “What can we do better? What should we have in place?” And one of the things I encourage them to do is assign somebody to really stay on top of the industry and understand what’s going on in the world of large and small companies in that industry — why margins are terrible, why there’s a lot of M&A activity, what segments are growing or are shrinking, or how agriculture factors into all that. Because all those things are real-life decisions that put pressure on food and beverage companies and that they legitimately do worry about. And I’ve seen instances where economic developers who can talk shop more effectively with somebody like me or my clients in moments where they’re coming down to a shortlist decision, really make them feel differently about their ability to help them get through the process of delivering a facility there.

Corde: This is a segment that has been changing, evolving, and growing tremendously over the last few years. Anybody that’s coming to the table now is really trying to play catchup at this point. Fortunately for Virginia, they’re not in that position. You guys have been one of the leaders in this space and you’re kind of in the driver’s seat. But staying on top of this industry, continuing to watch it evolve, continuing to watch those trends, looking out for those companies that are starting out with a great product, a great idea, great marketing, watching them as they start their initial phases most likely in a co-packer type of environment, watching that production start to grow, watching their product really start to gain some traction — those are, I think, the keys to staying on top of this industry and making sure that you’re finding those next generation of movers, those next generation of hot products — and really understanding which of those have staying power, which is most important.

Initial investment into this industry is tremendous. It’s not for the faint of heart. You can’t just go to market, build a giant facility and say, “Okay, great, we’re going to produce this product and it’s going to be wildly successful.” These companies have to start small, have to start with co-packing relationships. The number of those facilities that are in Virginia already is a great start, because a lot of these products are already being produced in a startup phase there. But staying on top of those and really developing and cultivating those products and trying to keep them home could be a major win.

For the full interview, visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts