Virginia's Rural Storyteller

A Conversation With Beth Macy

Beth Macy is a three-time New York Times-bestselling author. She is the author of “Factory Man,” “Truevine,” and “Dopesick,” books that tell separate stories, but all stories through which the challenges, issues, prospects, and hopes of rural America are studied in different ways. Macy was a reporter for The Roanoke Times from 1989 to 2014. VEDP President and CEO Stephen Moret recently visited with Macy in Roanoke to discuss her work and unique perspective on issues facing rural America.

Stephen Moret: Beth, you have a unique perspective, having written books that talked about some of the challenges facing rural Virginia, which are largely the same issues faced in the rest of rural America. Tell us about your background and what drew you to telling these difficult stories.

Beth Macy: I’m from a little town in Ohio called Urbana. Not very urban, despite the name of it. I was the first person in my family to go to college. I went fully on financial aid; we were so poor, I got money left over at the end to buy my books with.

Moret: Where did you go?

Macy: I went to Bowling Green State University for undergrad. That, more than anything, changed my life. I have more than paid back those grants and scholarships, times a hundred. And it’s shown me just how hard it is for people to get out of poverty.

I’ve always had a heart for outsiders and underdogs because I was definitely an outsider, I was definitely an underdog. I consider myself that last generation able as a poor kid to go to college and have it be totally paid for — mostly with government grants, but I worked three jobs, too. So I just have always written from the point of view that we don’t all start out at the same place, and when we’re generous, when we help others come along behind us, we all prosper and profit.

Moret: How early did you know that you wanted to be a writer?

Macy: I loved English class in high school. But I had a paper route, the only little girl that had a paper route in my little town. And I used to go around and spend a lot of time collecting. So, think about all the skills you learn as a reporter and a writer and a negotiator, just going out, talking to strangers. Pulling out of them their stories. Everybody has a story if you dig deep enough. Many were lonely older people, so I learned to talk to all kinds of people. I also learned that people weren’t exactly as they presented.

Moret: As economic development practitioners, we’re drawn in particular to the book you published in 2014, “Factory Man,” which takes a look at the effects of globalization on the furniture industry in rural Virginia through the lens of Bassett Furniture and related companies.

One of the things I think is really special about this book is that the story told, while it is unique to Bassett and that particular community, has many themes that relate to rural development and the challenges of shifts in manufacturing as a whole over similar periods of time. The concept of a factory town, especially in the South, how one employer influenced that town. So many small towns have been dominated by a single major employer and source of jobs. We saw that in Virginia with the furniture and textile industries which were once huge creators, now quite small compared to what they used to be. I think about Danville and those big hulking facilities that are still there, hoping to perhaps one day be revitalized with new industry. What do you think the future looks like for small towns like those places in Southern Virginia?

Macy: It’s pretty shocking when you just go back a few decades. They used to say Martinsville had the highest per capita number of millionaires in America. I mean, it was Virginia’s economic powerhouse — it was our factory floor, if you will. People used to say you could quit your job that morning and get another job by noon. One person told me they had three jobs in one day. One person said, “What we need is some unemployment around here.”

And when I set out to write about what was happening in Martinsville, I didn’t have a big agenda. I was still writing for The Roanoke Times. All I knew was that Martinsville had had the highest unemployment rate in the state for at least 12 years, and I wanted to see what that looked like. Nobody had ever tallied up all the losses. Just every time a factory closed they’d say, “Stanley Furniture is going out, that’s going to put...” The last story was 600 and some people were going to lose their jobs. Nobody said, “That’s on the heels of…” and added them all up.

And not just those jobs, but also where the people spent their money. That means the mom-and-pop diners, all the furniture stores, the little places where people spent their money went out of business, too. When you added them up, on the ground that looked like — I got this from the Martinsville-Henry County economic development data cruncher — 50% of the jobs had gone away. Among those people who were still working, most of them had to drive outside of the county for work.

So, my job when I first went down there was to answer this question: What happens when half of your jobs go away? What does that look like on the ground? So I went to a food pantry where people would line up two hours before the doors opened. Disability rates had gone up 64.1% just since China joined the WTO in ’01, just in Martinsville. Food stamps had tripled. It was shocking.

And as I was finishing up the reporting on that, the police were saying, “Drug crime is through the roof.” People committing crimes were desperate and unemployed. But many of them were committing crimes because of their fear of being dopesick. I didn’t really get the connection between opioid use disorder and what I was reporting until much later. By 2015, Case and Deaton, those Nobel-winning economists, dropped their bombshell study showing that for the first time in America, life expectancy was going down.

Moret: One of the things you explore in “Factory Man” is how low-cost Asian imports caught the furniture industry off guard. You go into some of the impacts those imports have on industry, workers, and the towns they called home. What stood out to you as you started digging into those issues, and the impact that that sort of trade situation had on places like Martinsville?

Macy: So many things stood out. I first set out just to describe what it looked like, the aftermath story. When I was doing some early reporting, I interviewed a friend of mine just on background. “Tell me everything you know about the furniture industry.” Of course, he described how the textile plants started closing in the ’90s and going to Mexico and Central America in the wake of NAFTA. And then the WTO in ’01. And how the furniture factories went next after that.

What was interesting about “Factory Man,” and I found this in that first interview, was my friend said, “Well, you know, there’s somebody that didn’t close their factory.” Everybody else did this thing, John Bassett III did something else. And not only that, he was successful. He sued China in a court of international trade to keep his factory going. Wasn’t exactly a lawsuit, but he petitioned the government to investigate whether the Chinese were cheating, not abiding by the WTO rules that they said they would. He found out that they were, in fact, cheating.

He basically went against members of his family back at Bassett Furniture. Members of the industry, a lot of people were already so invested at that point in off-shoring, they didn’t want him to succeed because they would have to pay higher duties for the imported goods coming in. And he’s saying, “But what about these families here? What about those families that made our family rich? Don’t we owe them something?”

Moret: So you can think of that as a case study for, at least partially, the unintended effects of trade. Now we have trade more front and center in the political debate than it’s been in a long time. Can you describe the core thing they were doing with respect to cheating?

Macy: They were dumping. There are many definitions. But the main one is selling a product for less than you paid for the goods to make the product.

I have always written from the point of view that we don't all start out at the same place, and when we're generous, when we help others come along behind us, we all prosper and profit.

Moret: Are there any lessons you think we can take from that for what might be happening now, or what could happen in the near future?

Macy: As I was writing the prologue of the book, the line came to me that nobody was minding the backroom of this new global store. The WTO was supposed to, but it cost millions of dollars for an industry, like the bedroom furniture industry in this case, to hire lawyers to make sure that they investigate this charge of illegal dumping.

We have to have a system in place. Because by the time a factory realizes they’re competing against people who are cheating, that are literally breaking the law they signed onto, they’re already in a bad financial spot. Only somebody like John Bassett, with a huge chip on his shoulder because of the way he had been treated in his family and his industry, would have the chutzpah and money to prove his case. By the way, he was born a millionaire.

Moret: Your latest book, “Dopesick,” takes a look at the opioid epidemic in America, which as you noted earlier is quite a correlation with many of these towns that have had dislocation of their major employers due to trade and automation. It’s particularly acute in rural America, where often traded goods are over-indexed in those communities, where a single sector or even a single employer is the major driver. Can you talk about what you found in writing and researching “Dopesick,” and what impacts you may be seeing in folks’ ability to enter and stay in the workforce? Also, could you expand on where you see this going? It seems like America’s only now starting to wrap its head around the scope of the problem. I haven’t followed as closely as you have, but it doesn’t seem to me that it’s started getting better yet.

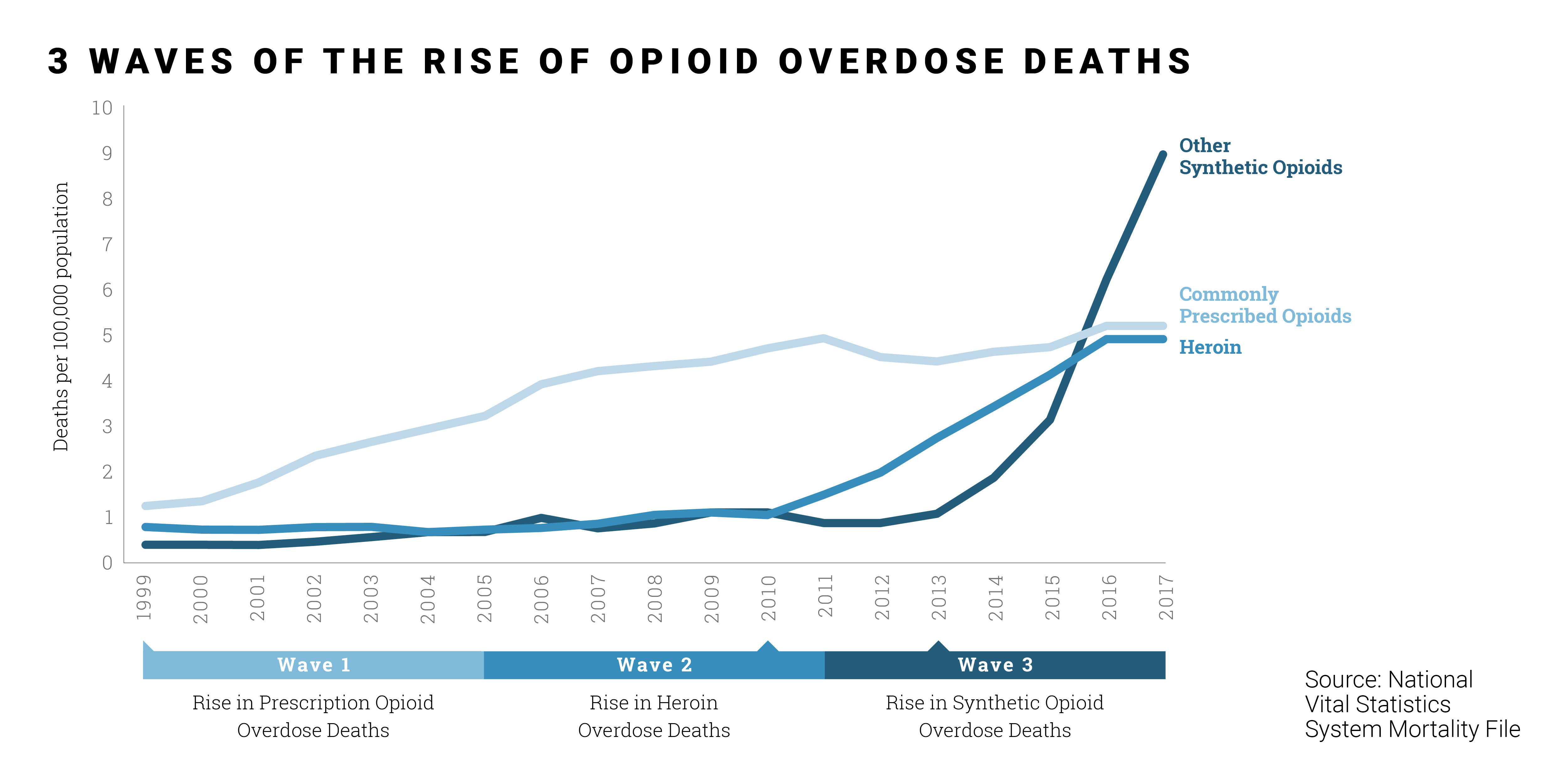

Macy: The number is still through the roof, with 2.6 million Americans addicted. One in five people who have a heroin or opioid addiction have access to what science says are the best treatments, which are buprenorphine or methadone. I call it MAT in the book for medication-assisted treatment. There’s still a real scarcity of that, especially in rural communities where overdose death rates can be as much as 65% higher than the national average and in urban areas.

There are a lot of reasons for that. The first reason it’s worse in rural areas is because it’s been happening longer there. Pharmaceutical companies literally targeted rural areas because they bought data that showed them which doctors were prescribing competing opioids. They knew that Dr. John Smith in Martinsville or in Galax or in St. Charles, Virginia, was already prescribing a lot. There were legitimate workplace injuries because of the factories and tough jobs, mining and what not.

So they went to those doctors and, using false data, they claimed that their new drug, Oxycontin, was safer than the competing opioids. “You should prescribe this.” They also funded trade groups — they call them astroturfing groups — to say these drugs are safer, too. They flipped the narrative that we had known for 100 years, that opioids were addictive and only to be used in end of life, cancer, and very severe pain post-surgery. So now, “Opioids are safe to use for moderate back pain, bronchitis pain, sore throat, TMJ.” I mean, anything went.

They purposefully targeted rural areas because the data showed that’s where the biggest need was. And the army of sales reps they hired was incentivized to get doctors to prescribe ever-higher doses. They got bigger bonuses the higher the dose.

Then you flip all that on top of the job losses and areas that tend to be more conservative and where treatment isn’t readily available.

And you add that cultural element. “We’re from Appalachia, we’re country people, we’re tough, we should be able to kick this on our own.” It’s just a nightmare in these communities.

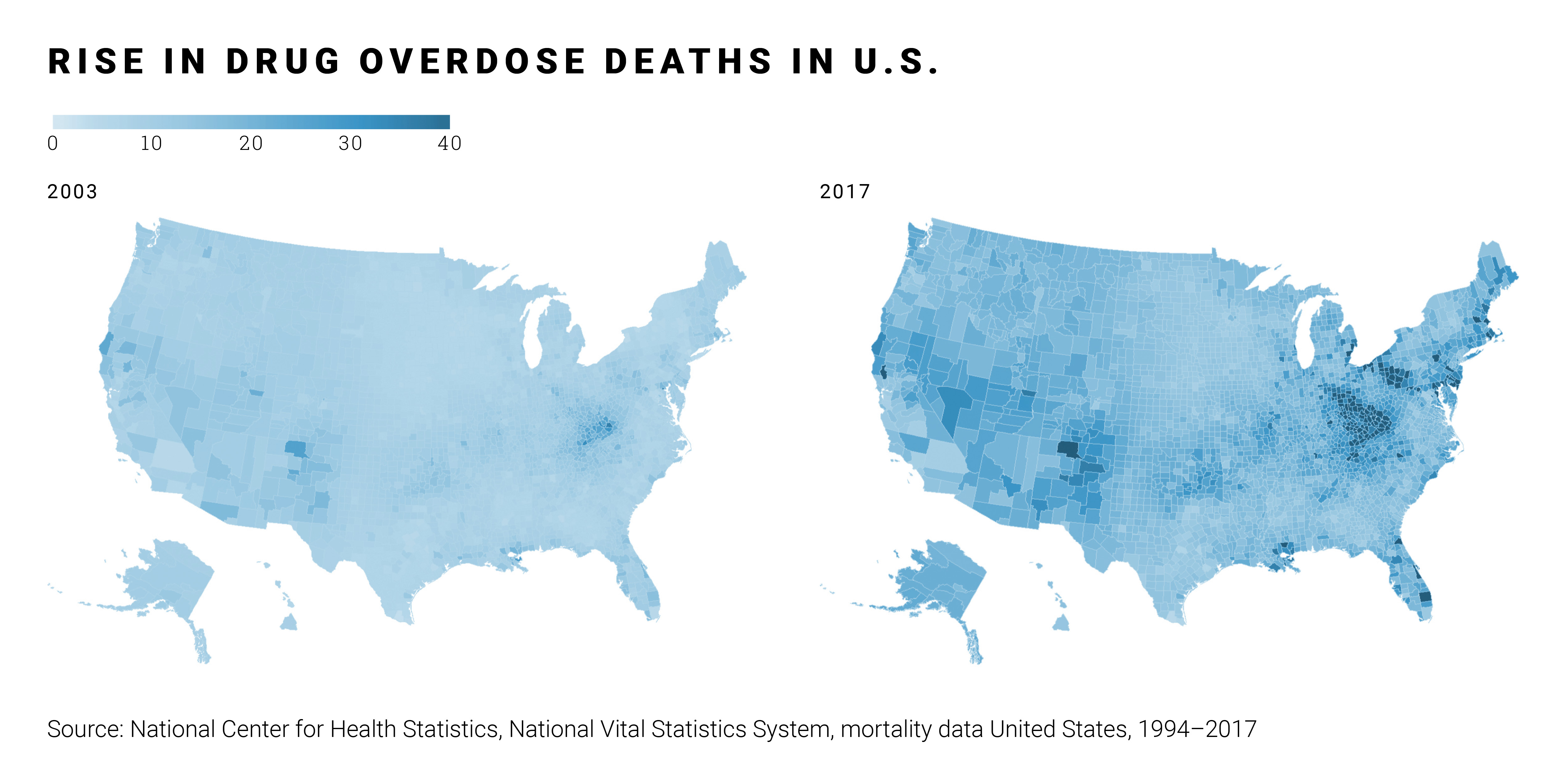

More than 70,000 Americans died from a drug overdose in 2017.

Moret: What do you think is the answer, and where’s action needed the most?

Macy: That’s a good question. When I finished the book, I didn’t want to write about this ever again. It was so depressing. In the year since, I’ve been reporting on solutions. I have a piece coming out in The Atlantic this fall about a kick-ass rural treatment provider from Appalachia who is now working in a small town. She’s figured out that the main place where people die is this fundamental dissonance between treating the addicted person as a person worthy of medical care, and treating them as a moral failure or a criminal.

In a rural county so small in Indiana that they didn’t have money to fund a drug court, she talked the judges in her courts into allowing her to set up a treatment center in the courthouse. That forced the probation, the law enforcement, and the judges to talk to the social workers and treatment providers.

The people have to have jobs; they help them get jobs. They have to have Medicaid. I don’t think this would work in a non-Medicaid expansion state, so, yay, Virginia! And they have to pass all these drug tests, four times a week, random, so they never know when they’re going to show up. For the first time, they’re breaking the cycle of people getting out of jail, having a dirty drug screen, going back to jail. I think it’s something that could be replicated in small towns everywhere.

Drug courts are great. We have 3,300 drug courts in America, but they’re mostly in urban areas. A lot of rural areas can’t even afford a drug court.

Moret: Wow. So there may be some hope in front of us.

Macy: There may be some hope.

Moret: Stepping back for a second, the theme of this issue of Virginia Economic Review is all about the great American rural growth challenge and how Virginia hopes to be the first state in the country that positions each of its regions for growth. Maybe not the same level of growth, but for sustained growth.

We certainly have a number of great things happening in Virginia with broadband investment, site development, workforce training. A lot of different issues are being tackled. Based on what you’ve seen and reported in your books, I’d be curious if you have any thoughts about what the state and/or localities and regions could do to help achieve that goal of positioning rural Virginia, and some ways rural America, for growth?

Macy: I think we have got to get our arms around this opioid crisis. A Pew Center Survey said most Americans think it’s the number one drug addiction issue facing America. We need some leadership on this issue. Where I see successes happening are on the ground. They’re these rural innovators who are taking this issue on for a variety of reasons.

I just interviewed, down in Mount Airy, N.C., a retired DEA agent, Marine Corps sergeant, and law enforcement officer. He came out of retirement to head the opioid response in Surry County, which has the highest rate of overdose in North Carolina. Now, this is Mayberry, literally, the town where Mayberry of “The Andy Griffith Show” was based. He’s saying nobody’s collaborating. The hospital doesn’t know what the jail’s doing, doesn’t know what the town council’s doing. Little efforts are being made, but none of it is being curated from above. He was hired to do that.

That’s a really cool example of somebody that law enforcement respects, because he’s one of them, really figuring out a way to get people to work together. I think if we had more leadership on the state and regional levels, these things would be more likely to come about.

Moret: So, essentially, more effective addiction treatment would help lead us to a place where you have more people who are really able to be productively employed, and that would be a big contribution.

Macy: That would be huge. It would be huge.

Moret: There’s a miniseries coming up with Tom Hanks. Can you talk about that at all?

Macy: I can talk a little bit about it. It was originally going to be an HBO four-hour limited series, like the company did with “Olive Kitteridge.” It’s now with a film production company. Still, Tom Hanks is attached and wants to play John Bassett, because who wouldn’t? The screenwriter is very well-regarded, a Pulitzer winner. He wrote “Doubt” and “Moonstruck” and his name’s John Patrick Shanley. It’s still in development, they’ve hired a director, and I’m still pretty hopeful about it.

Moret: We can’t wait to see it. I think the combination of your wonderful story with one of America’s favorite actors is going to be really special.

It’s a wonderful story, we’re so grateful that you made time to be with us today. We’re hoping to pull off perhaps for Virginia what John Bassett pulled off for his company.

Macy: That’d be awesome.

For the full interview, visit www.vedp.org/Podcasts