Citizens and consumers will feel these harms personally. Hijacked thermostats and smart fridges could malfunction and make it impossible to use home appliances. Hacks of connected insulin pumps and heart monitors only increase the potential for cyberattacks to cause real-world physical harm. Information collected by these devices contributes to future data breach risks as well. This is the motivation behind Virginia’s new statewide IoT cybersecurity contest open to college faculty, graduate students, and undergrads: designing new cybersecurity protections for connected devices. The Commonwealth Cyber Initiative also funds research projects dealing with security for these devices.

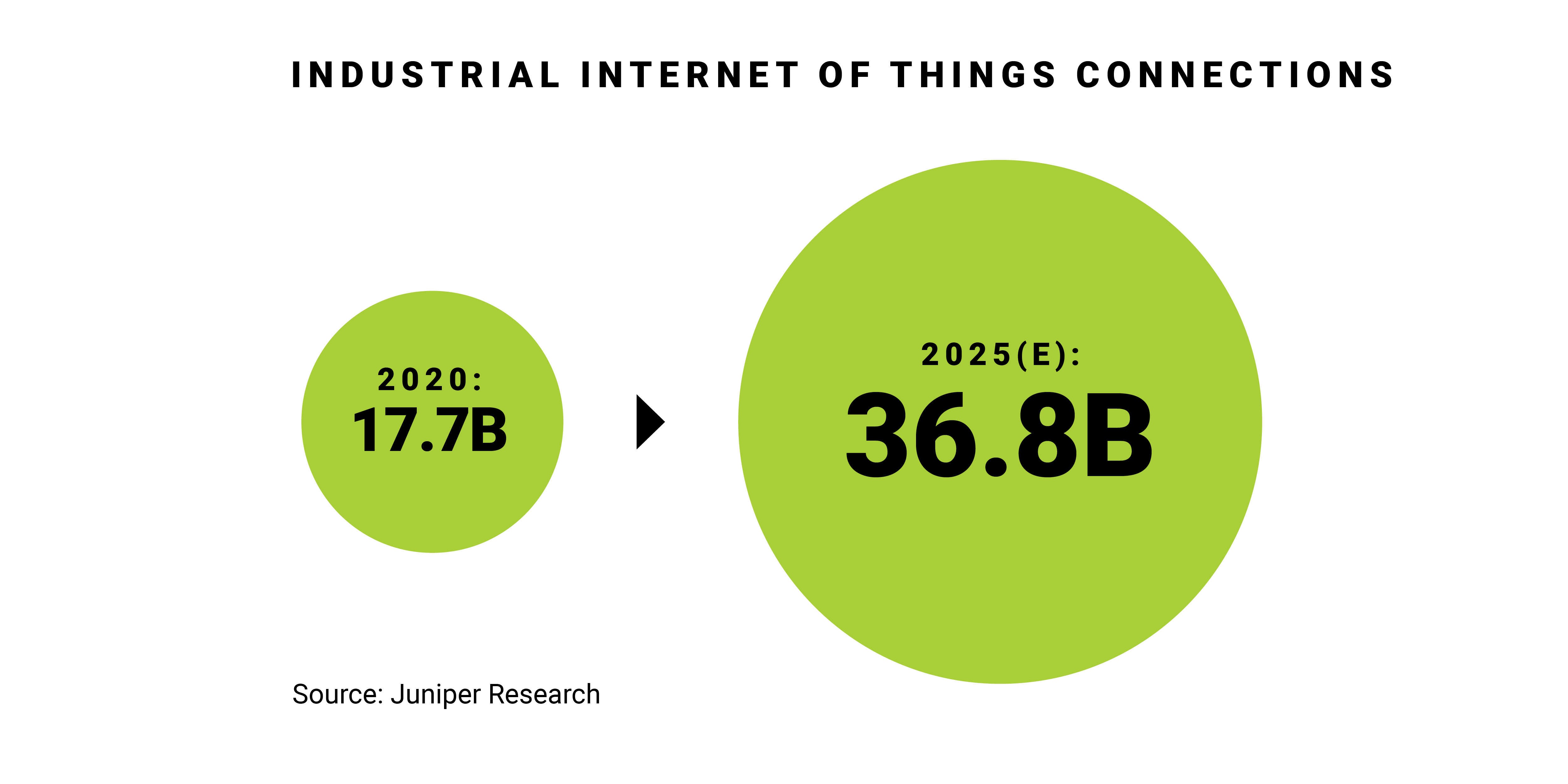

Yet these changes, and risks, are not confined to the home. Industrial and manufacturing facilities — from energy grids and oil pipelines to vehicle factories and water treatment plants — are digitizing their business functions, too. In the process, many so-called industrial internet of things (IIoT) devices link these physical systems directly to the internet. Market research firm Juniper Research, for instance, predicted that IIoT connections would rise from 17.7 billion in 2020 to 36.8 billion in 2025, representing a massive public and private investment in this technology.

Connecting industrial systems online is compelling to businesses. The operator of a water treatment plant can get real-time data from chemical sensors; safety personnel on a factory floor can remotely deactivate machinery from their devices. Digitizing old, clunky industrial systems promises cost reduction for companies alongside potential gains in safety and system control. More connectivity brings more risk, and a rapidly growing market offers protections for these systems that manipulate the physical world.

Shifting Threat Vectors

Newfound connectivity is not the only problem facing digitally connected citizens, businesses, and government agencies. Cybercriminals’ growing use of ransomware — which infects computers, encrypts data, and holds it hostage until victims fork over cryptocurrency ransom — is likewise shifting the cybersecurity landscape.

The nonprofit Institute for Security & Technology’s Ransomware Task Force wrote in its April 2021 report that ransomware “has disproportionately impacted the healthcare industry during the COVID pandemic, and has shut down schools, hospitals, police stations, city governments, and U.S. military facilities.” The East Coast’s major fuel pipeline, the Colonial Pipeline, was struck by a ransomware attack earlier this year, after which Virginia declared a state of emergency. Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia’s largest public school system, was itself hit with a ransomware attack in the fall of 2020.

Taking advantage of outdated, possibly unpatched systems is a serious problem as well. “Advanced persistent threats are using not only novel new techniques, but also older exploits that can prey on outdated technology to exploit public and private sector networks,” said Adam Maruyama, manager, customer success and federal practice lead for the Cortex Xpanse platform at Palo Alto Networks in Arlington.

Tracking and Responding to Cyber Threats

Business and government agencies increasingly need to track and respond to these cyber threats. It’s why threat intelligence, network defense, and incident response needs have driven a rapidly expanding national cybersecurity services market.

Nationally, firms like FireEye, CrowdStrike, and Palo Alto have rapidly grown in recent years to service clients across public and private sectors.

Virginia serves as a key nexus for this work. The Commonwealth has more than 650 cybersecurity companies in its borders, the most per capita in the country, according to the CyberVA Commission. Virginia-based cybersecurity professionals span private companies, universities, the nonprofit sector, and the United States defense and intelligence communities. Consumer website Comparitech recently listed Virginia as the top state in the country for information security jobs.

It’s not just companies and government agencies. FS-ISAC — the global cyber intelligence-sharing organization for the financial sector — is headquartered in Fairfax County. The nonprofit Global Resilience Federation that connects many cyber intelligence-sharing communities, and which grew out of FS-ISAC, is also based in Fairfax County; its members span five continents and numerous critical industries.

“Virginia is uniquely positioned to facilitate and host collaboration between the federal government and industry,” said Ernie Magnotti, chief information security officer at Leonardo DRS. “Government and industry need to get better at aligning in the fight. Virginia is the place where that alignment is happening.”