Tucked away in Hampton next to Langley Air Force Base, Langley Research Center is NASA’s birthplace. “It’s the nation’s first aeronautical center,” says David Young, Langley’s deputy director, who began working as a researcher at Langley in 1980. “Everything we do grew out of that.” It’s also a major driver of science, technology, engineering, and math education for Virginia and surrounding states, helping the next generation of engineers and educators build the future.

America's Original Aeronautical Center

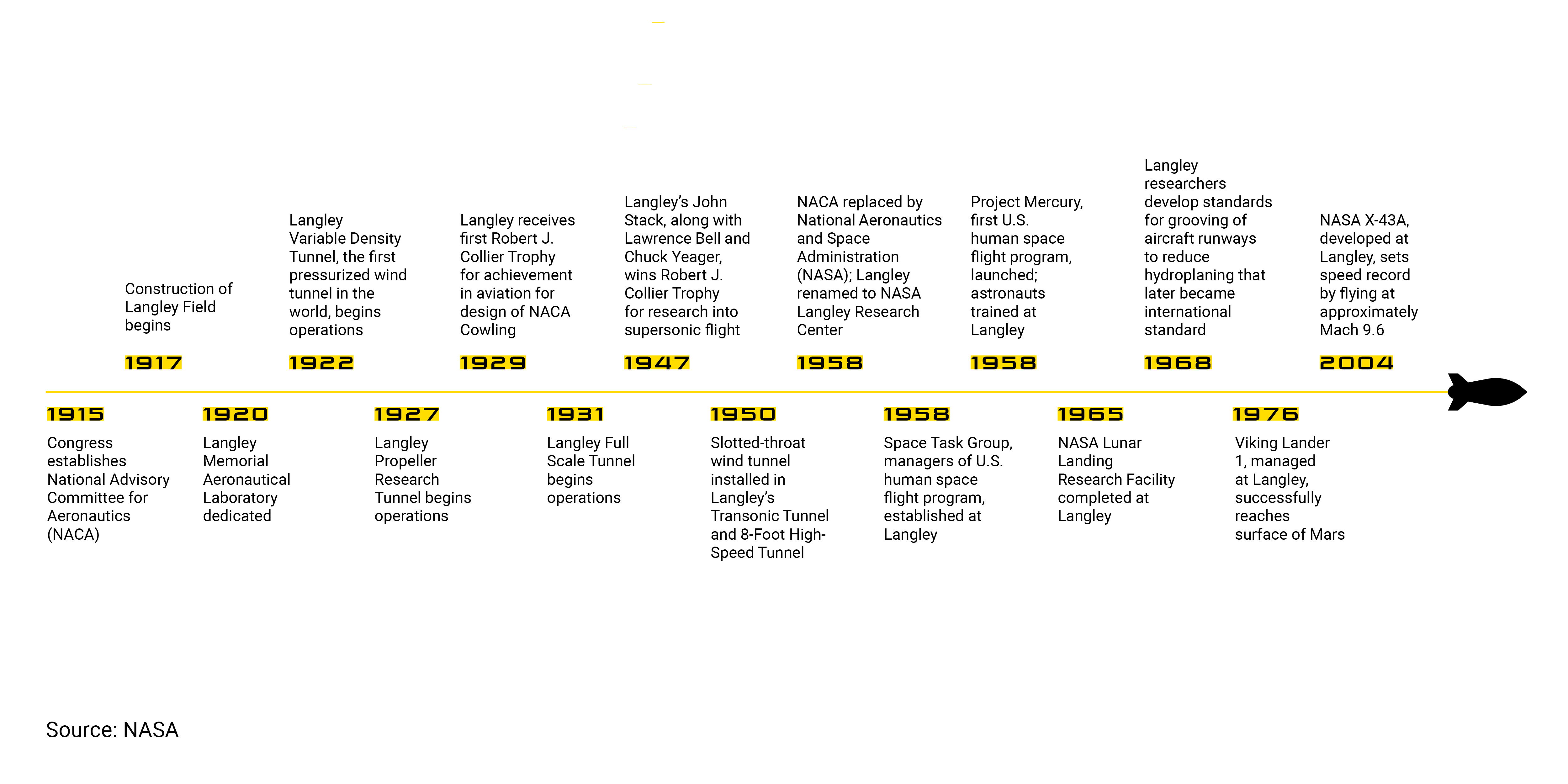

In 1915, responding to signs that the birthplace of powered flight, the United States, had fallen behind Europe, Congress formed the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA) with $5,000 in funding (about $125,000 in today’s dollars).

For five years, the organization languished without any laboratories or airfields. It broke ground on what would become known as the Langley Research Center in Hampton in 1917, but World War I interrupted construction. It wasn’t until 1920 that engineers built the center’s first wind tunnel. And then they wasted no time catching up.

In 1922, Newport News Shipping and Drydock Company built the world’s first pressurized wind tunnel, the Variable Density Tunnel (VDT), for Langley. The steel railroad size, capsule-shaped machine saw service for more than two decades, during which it made airfoil design studies still referenced by aeronautical engineers today. The retired VDT, designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985, now occupies a place of honor on display at Langley.

Thanks in part to the VDT and the other wind tunnels at Langley, “We’ve been a key part of development of every aircraft in this nation, whether it’s commercial or for the military,” Young says. “Every single aircraft you’ve ever flown on, every single aircraft you’ve ever seen fly over your head, was developed with Langley technology in it. Every breakthrough we’ve had in terms of aircraft design came through our wind tunnels.”

And the work doesn’t end with aircraft. “Because we have that deep understanding of aerodynamics and aerothermal, we’ve used that for planetary missions,” Young says. “We’ve used that for science and remote sensing. We learned how to measure the atmosphere, so we knew what we were flying through, and use that same technology to measure the Earth today.”

In 1957, Russia launched the first satellite, Sputnik, setting off a panic in the West. Once again, the U.S. had been left behind, and it raced to catch up. NACA became the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in 1958, and the space race was on, with Langley at the center of the action.

Reaching for the Stars

NASA introduced America’s seven Mercury astronauts in Washington in 1959. They trained at Langley. Also there, human “computers” did the math required to rocket them into space. Most of them were women, and among them were African-Americans Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Winston Jackson, immortalized in the book “Hidden Figures” by Margot Lee Shetterly and the 2016 movie of the same name. In June, NASA announced that it would name its Washington headquarters after Jackson.

After President John F. Kennedy tasked the nation with landing astronauts on the moon by the end of the 1960s, Langley developed the know-how that made it possible. Langley-based engineers John Houbolt and Bill Michael developed the so-called lunar-orbit rendezvous architecture that made the landings of Project Apollo possible with a single rocket launch each.

Today, wind tunnel testing and other crucial work for the Space Launch System and Orion capsule for Artemis, NASA’s next human-crewed deep space program, takes place at Langley.

Langley-based research also plays a crucial role in atmospheric studies. For example, data on the hole in the ozone layer captured by Langley-managed satellites led to bans on ozone-depleting chemicals. With an eye on the future, Langley has partnered with the Virginia Space Grant Consortium, five colleges and universities, the Center for Innovative Technology, and other Virginia institutions to provide educational and research opportunities in aerospace.