Ardent Craft Ales, Richmond

Virginia's first brush with alcoholic beverage production came in 1620, when English settler George Thorpe distilled the first batch of corn whiskey in what would become the United States at the Jamestown settlement near Williamsburg. Two of the Commonwealth’s most famous residents, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, attempted to distill beverages at their Virginia estates. Four centuries after Jamestown, the Commonwealth’s craft distilleries, wineries, and breweries are building on that history.

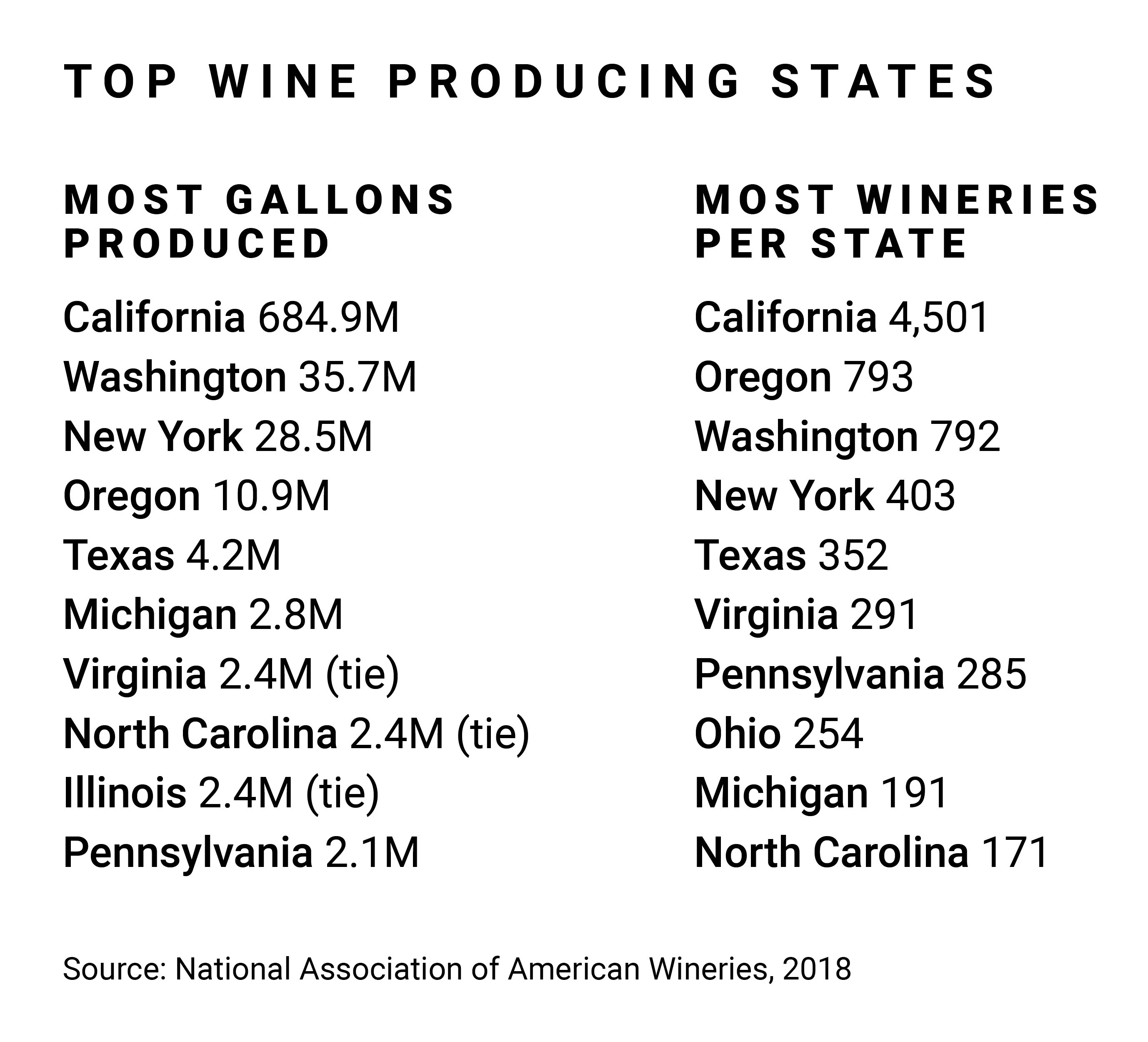

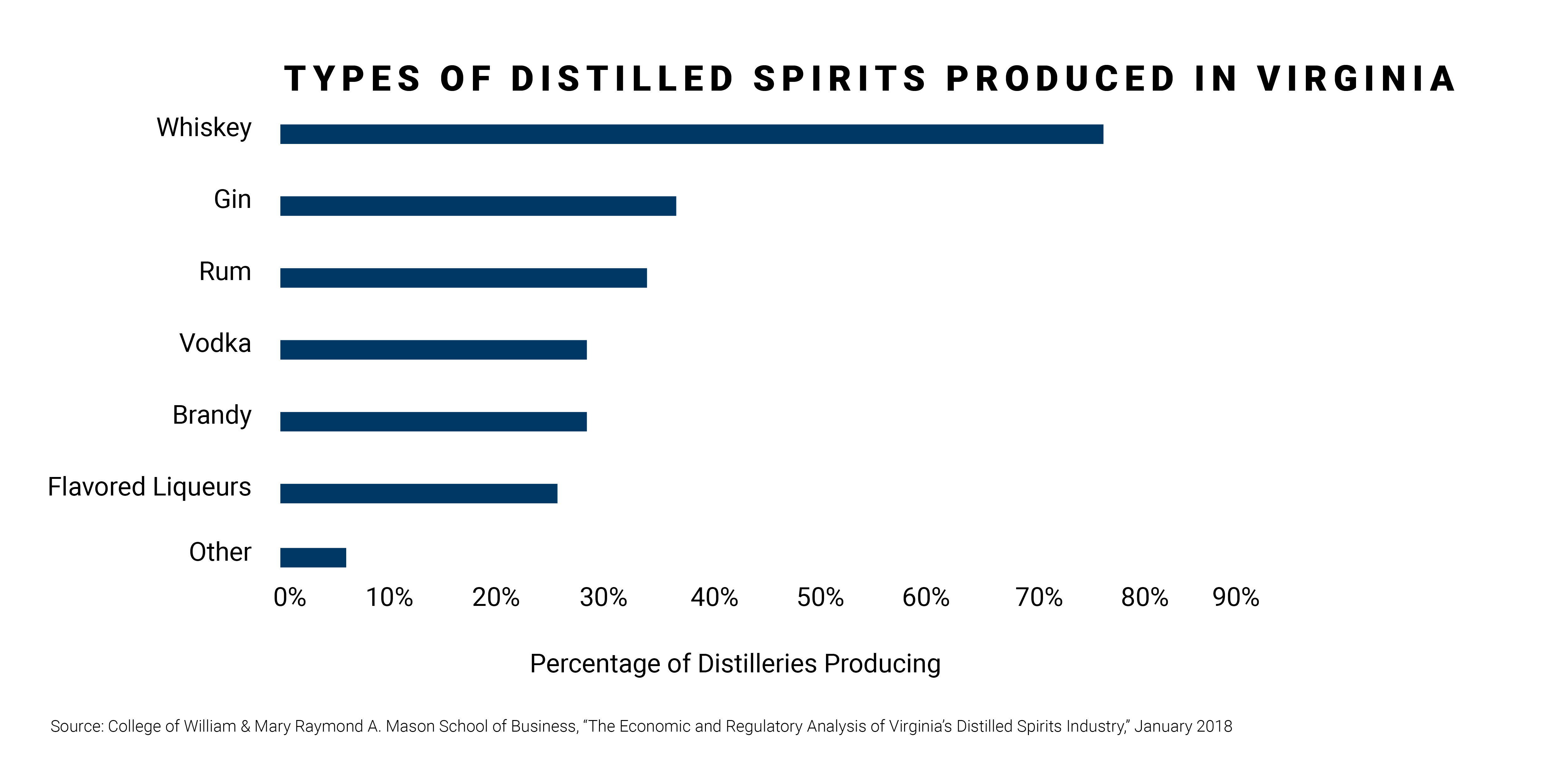

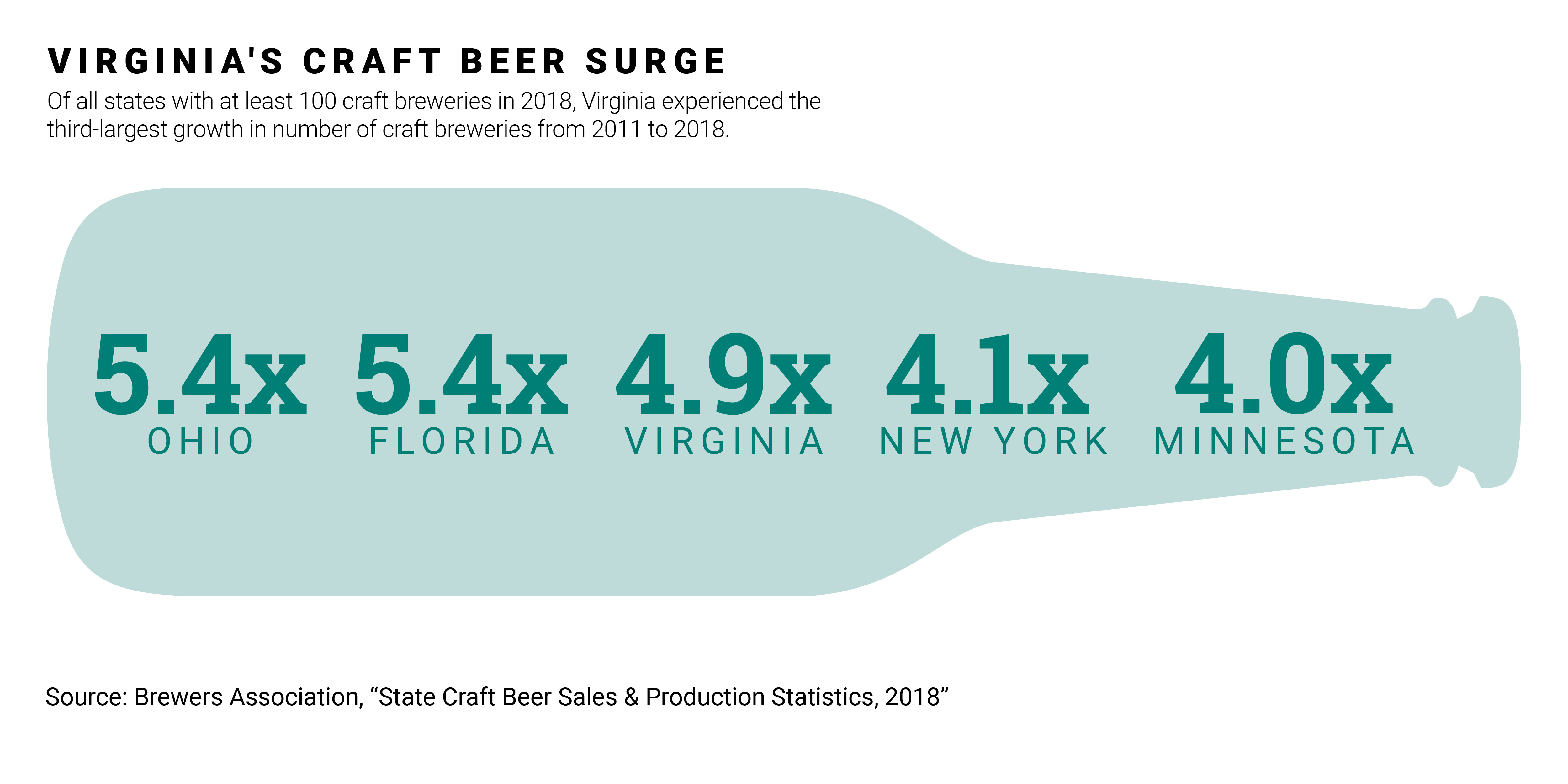

The Commonwealth has 291 vineyards and wineries, the sixth-highest total in the United States, and more than 70 distilleries, including the country’s largest craft producer of American single-malt whiskey (Virginia Distillery Company in Nelson County). Craft beer production has skyrocketed over the past decade to the point that VinePair.com, the internet’s most-read beverage website, ranked Richmond as the world’s top beer destination in 2018.

Virginia’s craft beverage producers are capitalizing on a national appetite for local products. A 2018 article in The Atlantic noted that the number of brewery establishments grew sixfold nationwide between 2008 and 2016 — during a time when U.S. beer consumption declined. In that article, Brewers Association Chief Economist Bart Watson said, “The craft beer movement was driven by consumer demand.” Craft distilleries, meanwhile, sold 7.2 million cases nationwide in 2017, with an annual growth rate of 23.7%, according to the American Craft Spirits Association’s Craft Spirits Data Project.

The keys to the rise of Virginia craft beverage production lie in a now-friendly regulatory environment, abundant resources, and an industry-wide spirit of collaboration.