Tangier Island Oyster Co., Accomack County

When Allen effectively produced disease-resistant oysters around 2003, oyster hatcheries realized a resurgence. In 2005, when VIMS released its first survey of shellfish aquaculture production, the state produced around 800,000 individual half-shell oysters. That number has quickly grown over the years, reaching 40 million oysters worth an estimated $62.4 million in 2018. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2018 Census of Aquaculture, one in every five American oysters sold in 2018 was harvested in Virginia.

Virginia’s 134 oyster farms made up 70% of all aquaculture operations in the Commonwealth in 2018, according to the same 2018 aquaculture census. Virginia is the top producer of hard clams in the U.S., producing around 200 million individual clams each year. All told, Virginia boasts 152 mollusk farms, nearly double the 80 in the Commonwealth in 2013 and trailing only Massachusetts’ 157. The Commonwealth’s $94.3 million in 2018 mollusk sales nearly tripled those in California, the second-highest state.

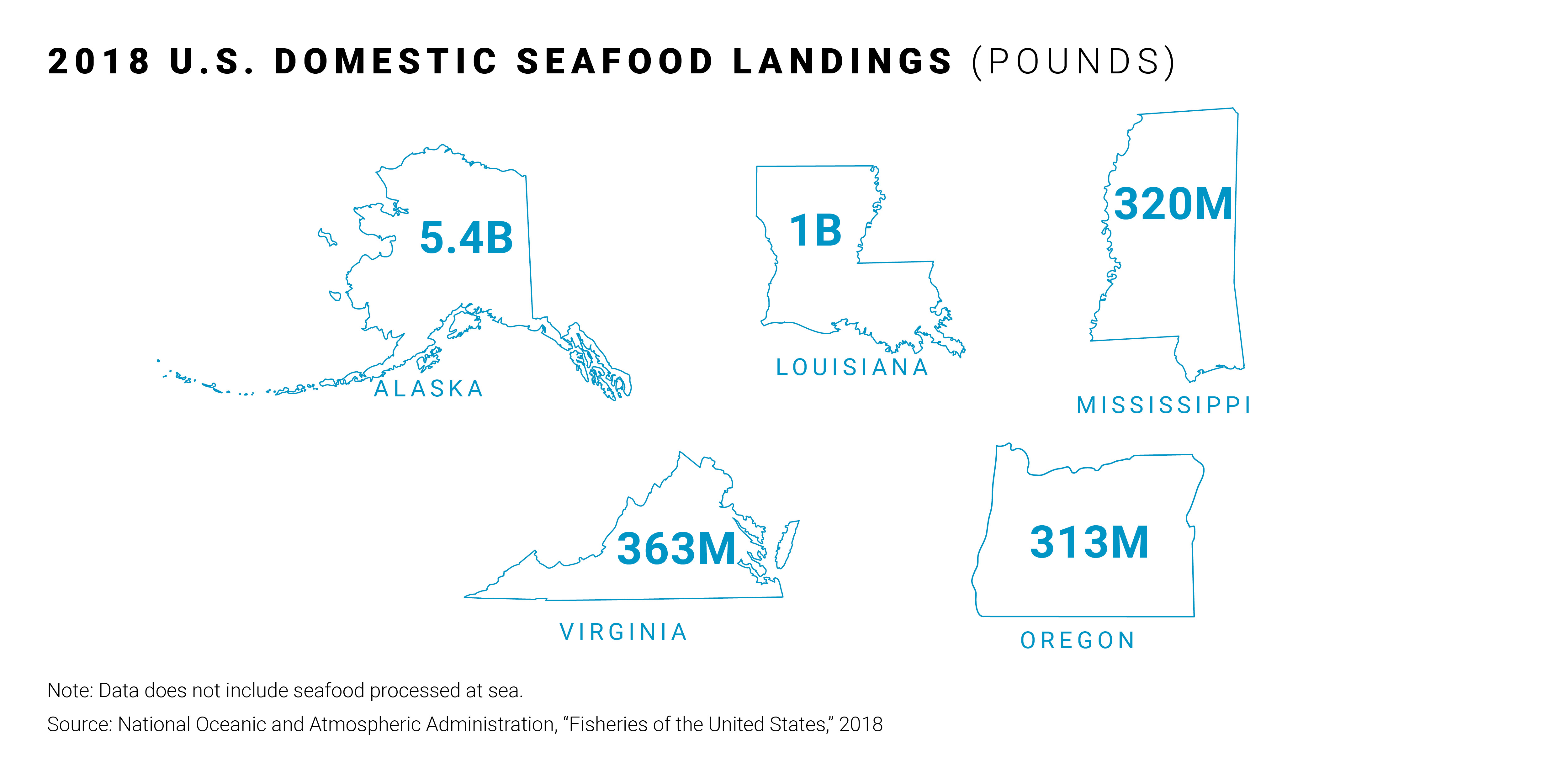

And it’s not just shellfish that the state is known for. A variety of finfish such as striped bass and flounder also proliferate. Virginia is the nation’s third-largest seafood producer, with total landings of 363 million pounds in 2018, outpaced only by Alaska and Louisiana. Sales of food fish in Virginia reached $15.4 million in 2018, up 35% over a five-year period.

The Port of Reedville on the Northern Neck was the fifth-largest port in the U.S. by volume of seafood landed in 2018. Meanwhile, the Seafood Industrial Park in Newport News has averaged in the top 10 nationally for value of seafood landed out of all seafood industrial parks. The massive park, home to a number of seafood and other water-dependent companies such as ice plants and boat-building businesses, provides full-service accommodations to the seafood industry, such as utility hook-ups and vessel fueling, service, and repair.